“The Union emerged from the war in stronger financial condition than it went in.”

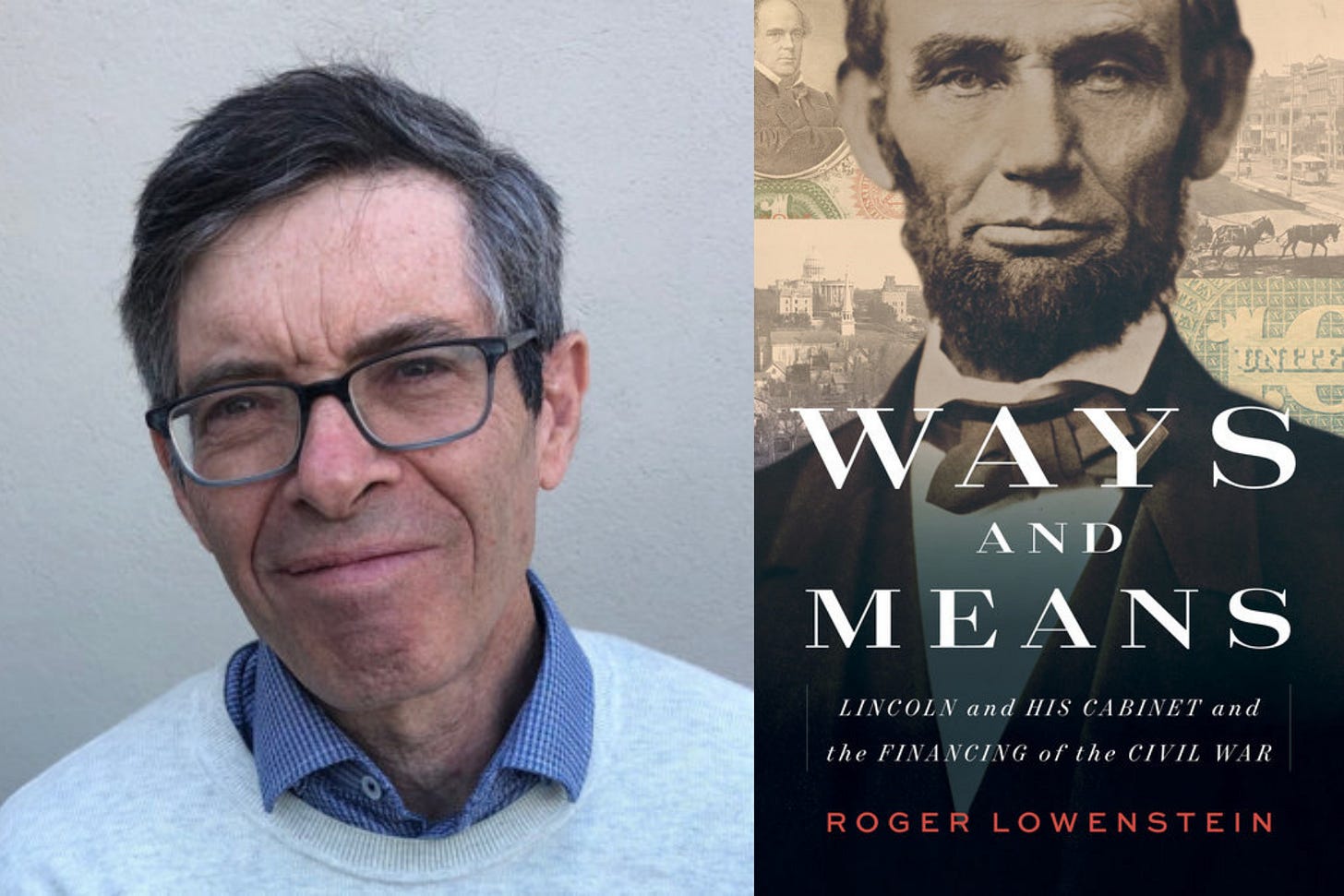

Part Two of a conversation with Roger Lowenstein, author of “Ways and Means: Lincoln and His Cabinet and the Financing of the Civil War”

This is the second of a two-part interview. Read the first part here. The conversation continues with Roger’s argument for how, in many ways, the Civil War was “already won” for the Union by early 1863, even though the conventional narrative—both then and now—suggested the opposite. The excerpts below have been condensed significantly and edited for clarity.

ROGER: The war went on for two more years, but the upshot was that the Union not only financed the war—it had been on the brink of default itself before the greenback came in—but emerged from the war in stronger financial condition than it went in. Its economy was stronger, its bond rating was higher, the interest rates it paid were lower.

Today, looking at the terrible war in Ukraine, we’re reminded how wars bring inflation. The Union survived the war with 80 percent inflation, which was a lot—it was painful—but it was no worse than the United States suffered in either World War I or World War II. Although there were two more years of fighting, [the North] had the financial piece pretty much solved by what turned out to be the midpoint of the war.

The South considered many of these steps and rejected them. They considered legal tender but were afraid to give their federal government’s imprimatur to any currency, so they just went with notes. They considered taxation, but they were reluctant to have federal taxation; their whole government was established on a states’ rights, anti-centralist view.

The third piece, inflation, became really terrible. At the beginning of the war, a barrel of flour was $5.50 in the South. By early spring in 1863—a time when the South is holding its own, or more, in the fight—a barrel of flour has gone up to $38. That’s 700 percent [inflation] compared to the 80 percent that the North would experience throughout the full four years [of the war]. If you take that forward another year, that barrel of flour [in the South] was up to $220. The numbers begin to get too crazy even to contemplate.

The South made other mistakes, all growing out of its anti-centralism and its arrogance. The South was a cotton cartel. It labored under the illusion that it had a cotton monopoly, something I think very similar to Vladimir Putin. We’ve seen how Putin thought that his control over energy supplies to Europe would give him carte blanche. However this war turns out, it’s really been tougher for the Russians—they’ve met with far more resistance over two months—than they expected.

The South preached high and low—they didn’t make a secret of it before the war—that thanks to cotton, nobody would dare make war on them. When the war started, the attorney general from Louisiana proposed that the South—while the sea lanes were still open [and] the Union navy didn’t [yet] have a blockade—ship cotton in great volume to England and sell it off as need be to finance a possibly long war. [Jefferson] Davis and his other ministers were so convinced that the war wouldn’t be long that they refused this.

In fact, they hit on a counter-strategy, which was to embargo their own cotton. They thought that if that happened, if the British and the French were starved for cotton, they would quickly put an end to the war—without even bothering to figure out how the Europeans would effect this [outcome], assuming that they would want to. This was a tragic, from the South’s point of view, economic mistake. It bled them of hard currency, depreciating the value of the notes many times [over]. And that meant that when they went to borrow, they just didn’t have the credit.

By the spring of 1863, they were starved for cash. The only thing left was to issue notes, and the notes were backed by nothing. They were having to divert their foodstuffs to the troops. In April of 1863, what I would call a turning point, the women in Richmond [the capital of the Confederacy] rioted. They broke open the stockades where the flour was stored to be shipped to the troops because they were starving. Many of their kids were starving. And some of them were actually arrested. You obviously can’t fight a war very well if the mothers and wives and daughters of the troops are being held in a stockade or starving. From this point on, desertion became a very serious problem. No one’s going to fight for a government [that] is failing to feed its people on the home front.

This economic disparity only continued, even as the South continued to hold its own [on the battlefield]. As late as a year and a half later, in July of 1864, the fourth year of the war, people are telling Lincoln he can’t win reelection. They’re urging him to go make peace with the South. Grant is still stuck in the mud, this time the mud of Petersburg, Virginia. But by then the South is totally bankrupt. The price of flour is now near $1,000 per barrel. And they were lost.

ADAM: It’s been a long time since I learned about the Civil War in school. But I distinctly remember the narrative that we learned, which was basically that the Union had nearly lost the war by early 1863. While that’s obviously far from the worst misimpression or alternate history that an American student can be taught about the Civil War, I’m still fascinated that that interpretation of events has had such staying power. And I wonder why you think that that narrative of doom and despair took hold so strongly at the time, and why it persisted.

ROGER: It’s not completely far-fetched in this sense: The South didn’t have to win. Robert E. Lee was never intending to “win” in the sense of capturing Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York. That was beyond him. His goal was, in his words, to make the North feel the evils of war, to make the Northern people suffer and end its tolerance for fighting. If you’re not victorious for long enough, it’s almost the same as losing.

In 1863 Lee made the incursion into Pennsylvania and fought in Gettysburg. I don’t think he got far enough then to vindicat[e] that narrative [that the Confederacy was close to winning the war]. I don’t think the North was as close to giving up the fight as people say, although the draft riots, which were really race riots, in New York that summer testify to the real unhappiness [among] white lower classes in the cities to fighting this wider, prolonged war.

But by the summer of 1864, there was a lot of pressure on Lincoln to form a peace. Lincoln had written out private instructions—sealed for his cabinet—in the event of what he expected would be his defeat [in the 1864 election].

ADAM: This is a very loose analogy that I’m going to make. But the first thing that came to mind when I was reading this part of the book was the 2020 presidential election. There was plenty of stressful uncertainty on election night, but by the early hours on Wednesday, it was pretty clear that Biden was going to come out ahead. At the very least, given his performance in some of the key swing states and the overwhelmingly Democratic cities and counties in those states that were still counting ballots and reporting, he had a good chance. Certainly a far better chance than the conventional wisdom that quickly took hold among Democrats between Tuesday and the weekend, when the major outlets finally called the race.

Some of that was a determination, I think, not to repeat the overconfidence of 2016. But it was still a really telling example of the actual facts on the ground differing in a really profound way from the accepted or the projected facts. You’ve covered business and financial markets for decades, so you’ve probably seen the same phenomenon play out time and time again. And I wonder what you make of all of this. Maybe it’s just human nature, when the accepted interpretation of events diverges so dramatically, or at least in some really fundamental ways, from the facts on the ground.

ROGER: I think one thing that’s happened with the populist nationalists or populist xenophobes—take your pick—Donald Trump being example number one in this country, but [Marine] Le Pen in France, the Brexit vote in [the UK], [Viktor] Orbán in Hungary, and so on, is that they’re much stronger than the people who believe in globalism and liberal democracy believed. In repeated elections, they’ve been stronger than even they themselves were willing to tell pollsters.

FiveThirtyEight wasn’t wrong about the 2016 election. I think they said there was a 30 percent chance of Trump winning. That was probably a correct call. He hit the three in 10. He got his votes in the right places. I think by 2020 we had seen so many examples of a three-percent edge in the polls not being enough to win. I think that’s also why people were pretty scared about [Emmanuel] Macron.

A much more benign populist, but he was a populist, was Harry Truman. He pulled off quite an upset. I have a feeling if you map where he got his votes, they wouldn’t look that different from where Donald Trump won his votes. [Thomas] Dewey [Truman’s opponent in the 1948 election] was a liberal Republican, a globalist, an internationalist. Farm country back then was Democratic country. It was the New Deal that had saved the farm districts, and they weren’t so willing to give up on Harry as all the newspapers thought they would be.

Lincoln in 1864, although he won a much bigger majority, all that really happened in 1864 compared with 1860 was 11 states weren’t voting in the Northern election. American political geographies are very hard to move.

Trump is essentially like the Confederacy. I’m not saying Trump is pro-slavery, but Trump is backward looking. His whole thing was looking back to the halcyon past that never existed. It was antebellum in that sense. It has a persistent appeal. The forces of modernity, so to speak—that’s why they’ve learned to be cautious.

To see more of Roger’s work, subscribe to his newsletter, Intrinsic Value, or visit rogerlowenstein.com. You can (and should!) get your copy of Ways and Means wherever books are sold.