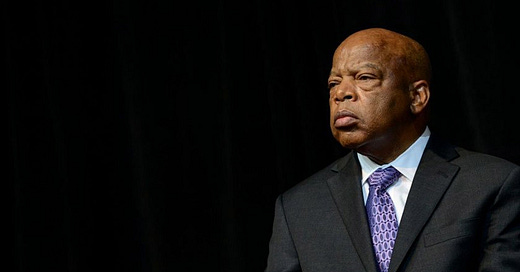

Remembering John Lewis, America’s Pilot Light

Two stories about a man who always kept the faith.

This article was originally published on Medium.

“Without a doubt the greatest living American.”

YouTube comments are not usually where one finds a meaningful analysis of American history. Or a compelling argument. Or really anything of substance. But there, underneath a decidedly non-HD video of Congressman John Lewis giving a speech to what I think was a health care advocacy organization, was a line that said it all: “Without a doubt the greatest living American.”

I came across that comment sometime in early 2012, during one of those magical nights when the Internet manages to do exactly what the tech CEOs promise: deliver connection and inspiration, even joy. I was living in a studio apartment in Washington, DC, and working on Capitol Hill while taking graduate school classes in the evenings. I don’t recall what sequence of links led me to that video, which in turn led me down a beautiful online rabbit hole of John Lewis speeches. What I do recall is thinking, as I watched speech after speech, Why aren’t these the most-viewed videos on the Internet?

Here, I thought to myself, is Congressman John Lewis, a witness to and shaper of history, a leader of the civil rights movement, a friend of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy.

Here is the “Conscience of the Congress,” the youngest speaker at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

Here is the man who had his skull fractured during the 1965 march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge near Selma, Alabama — the bridge that still bears the name of a Klansman but that will someday be named for John Lewis — on the day that came to be known as Bloody Sunday.

Here is this crusader for justice, this soft-spoken man with the voice that could boom. Here he is with his humility and his deeply earned assuredness and his steadfast conviction, having long since surrendered to what he called the “Spirit of History.”

Here, on YouTube, is John Lewis, the John Lewis, sharing his stories, his passion, his determination, his faith, his lifelong commitment to the struggle for, as he succinctly put it, “freedom, equality, basic human rights.” Sharing it with a small group here, a small group there, saying “‘no’ to hate but ‘yes’ to almost every invitation that landed in his box,” as Michele L. Norris wrote in the Washington Post. Sharing it all with the world, as he’d done selflessly and unrelentingly for decades.

A few months after this inspiring evening on YouTube, the same grad school curriculum I’d occasionally neglected so I could spend a night watching John Lewis speeches online called for me to write a paper about leadership. I emailed Lewis’s Washington, DC office and explained my situation as a Hill staffer and part-time graduate student. I asked if the congressman might consider sitting for an interview for my assignment.

A lot of offices would’ve declined a request like this. Given Congressman Lewis’s stature and renown, and the fact that I had zero ties to Georgia’s fifth congressional district, this was even more of a long shot. If I were lucky, I thought, maybe I’d get an email with some pre-written answers (which, to be clear, would’ve been more than adequate for my assignment).

But no. Just a few weeks later, I found myself sitting down with John Lewis in his office with a majestic view of the U.S. Capitol, the same U.S. Capitol he might have seen in the distance as he stood in front of the Lincoln Memorial in August 1963 and called on 250,000 people on the National Mall to “get in and stay in the streets of every city, every village and hamlet of this nation until true freedom comes, until the revolution of 1776 is complete.”

Nearly half a century later, on a steamy summer day in Washington, I was sitting down with John Lewis.

***

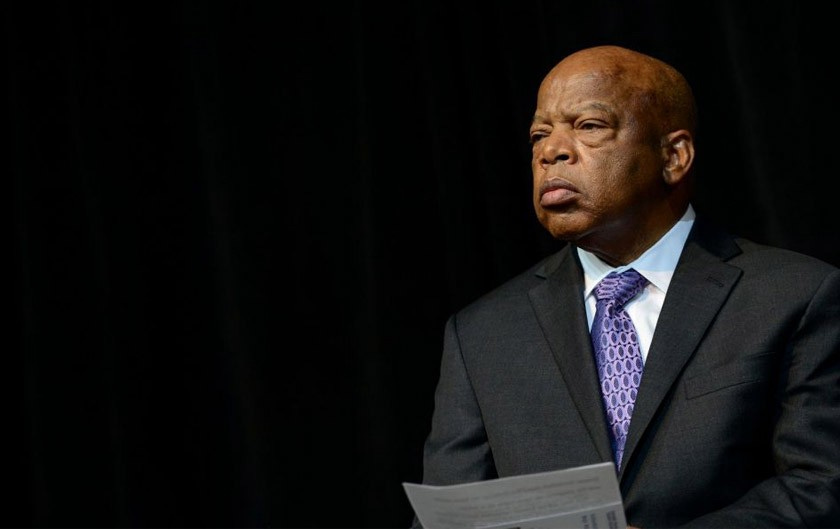

Many people have spoken of what made John Lewis such a remarkable person. It was more than his accomplishments, though those accomplishments were monumental. It was more than his bravery and courage, though the fear he faced down and the pain he endured are unimaginable to most of us. It was more than his willingness to get in “good trouble,” more than his lifelong dedication to the struggle, though that willingness and that dedication changed the world.

What made John Lewis remarkable, even beyond all of that, was his character. His decency. His kindness. His compassion. His presence. Not “presence” in the sense of fame or stature or prestige, though he had those things. Not the type of “presence” that is often used to describe the “proximity to power” feeling that emanates from a lot of political figures, though he was undoubtedly a powerful political figure.

The magnetism and beauty of John Lewis’s presence came from something much deeper, much more real, much more genuine. It seemed to come directly from his heart. It seemed to come from the fact that, in the words of Dr. King, he had been to the mountaintop, and he wanted to share with you what he’d seen. And somehow, no matter who you were, he was interested in what you’d seen along your journey, too.

This was “presence” in the most literal sense: the ability to be present in the moment. When John Lewis spoke with you, when he shook hands with you, when he smiled at you, you knew he saw you. He heard you. You mattered to him. Not as a political asset, but as a human being.

Wherever John Lewis was, when he was there, he was there. And on that day in July 2012 in the Cannon House Office Building, even though he had no reason to be there, he was there. All of him was there. That decency. That kindness. That compassion. That presence. The deliberateness and care with which he acted and spoke and gestured and chose his words. The focus and attention he somehow always made available for the person in front of him.

When I interviewed John Lewis about leadership, there was no question I could ask that he hadn’t answered thousands of times before. He had no need to engage with me, to share his wisdom and presence with me. But he did anyway.

A good leader, he told me, “must be a headlight, not a tail light.” A good leader must be there for the long term. You “can’t be a firecracker leader and shoot off and be gone,” he said. “You must keep burning.” Leaders get their hands dirty, Lewis told me. They get in the ring. “A leader must not call on his followers to do anything he’s not prepared to do,” Lewis said.

I asked him, of all the leaders he’d known and worked with throughout his life, a list that included presidents from Kennedy to Johnson to Obama, who had he learned the most from? Lewis didn’t hesitate. “Dr. King,” he said. “Dr. King inspired me to get in trouble.”

John Lewis and I ended our meeting with a quick photo before he moved to the next item on his busy schedule. That’s how a lot of political meetings end. But this conversation was unlike any other conversation I’ve had with a politician. It was unlike pretty much any conversation I’ve had with another person, for that matter.

Just think of the last time you had a conversation with anyone — let alone an elected official — who was truly present for you. In our world of too many distractions and too much to do, when was the last time you were truly present for someone else, especially for someone you didn’t need to help or listen to? I say that not to issue a blanket indictment of us but rather to celebrate John Lewis and his extraordinary presence. After all he had seen, done, achieved, witnessed, endured — after all of that, he still kept showing up for the human being in front of him.

I’ve never forgotten what John Lewis said that day. But I learned as much about leadership from what he did as from what he said.

***

Beyond their impact on culture and society, beyond the wisdom and progress they impart to the world, heroes and historical figures influence each of us in unique ways. Even if we don’t know them personally, we all have our own relationships with people we admire. The volume of tributes to John Lewis throughout his life and in the weeks since his passing reflects just how many people admire him, just how many people have their own special bond with this icon who they knew, marched with, read about, heard speak, saw around town, saw on YouTube, studied, loved.

Many of these tributes have been both genuine and genuinely moving. Some tributes, though, reflect the contradictions and hypocrisies at the heart of the American story. Some tributes have come from those whose beliefs, whose campaign contributions, whose votes in Congress, whose Supreme Court nominees, whose support for racist policies opposed everything John Lewis stood for. Everything he fought for. Everything he marched for. Everything he was arrested 40 times for. Everything he was beaten nearly to death for.

John Lewis knew these contradictions and hypocrisies well. He knew that “truth never did stop the concocters of racist ideas,” as Ibram X. Kendi writes in Stamped from the Beginning. As vividly and acutely as anyone, John Lewis had seen these racist ideas, been subjected to them, watched them mutate and transform over time, suffered their violent and unjust consequences. He probably wouldn’t have been surprised to hear eulogies from those who, as Joel Anderson wrote recently in Slate, “shamelessly celebrate the life of Lewis only to work assiduously to thwart his life’s work.”

John Lewis had seen and experienced too much along his journey to be surprised when a congressional colleague who posed for a picture with him one day endorsed racist voter suppression laws the next. Or when, as Ari Berman describes in Give Us the Ballot, on the very day in 2013 that the Supreme Court laid the groundwork to dismantle some of the most critical provisions of the Voting Rights Act precisely because they had been so effective, “a few hundred yards away at the U.S. Capitol, Congress unveiled a new statue of the civil rights leader Rosa Parks.” As if statues, but not voting rights, might be the solution to centuries of racial subjugation and discrimination. “The actual American history” of race, Kendi writes in Stamped from the Beginning, is one “of racial progress and the simultaneous progression of racism.”

John Lewis navigated these contradictions and hypocrisies all his life. As he wrote in his 1998 memoir, Walking with the Wind, “I don’t think that many political leaders are genuinely concerned about the problems of the poor, of blacks, of Hispanics, of the people in the inner cities. Yes, all politicians love people in general. They love humanity. But many of them are very uncomfortable with people in particular — especially up close.”

Lewis knew that the reverse could also be true for the politicians and powerful people who sought his friendship and association. They could like him — even love him — in person, as an individual, in particular. And they could do so while dismissing, demonizing, and disenfranchising people in general. Entire groups of people. Black people. Latinx people. Indigenous people. People whose background or love or faith or sexual orientation or bank account or bad luck made them appear different in the eyes of a white power structure. People whose exclusion from the system protected the system. People whose segregation from power served those in power just fine.

Part of what made John Lewis different, as a politician and as a human being, was that he loved people in general and in particular. He loved humanity, and he loved human beings. He knew the risks of this love. He knew he might be heralded for his immense capacity for forgiveness by some of those who chose to interpret that forgiveness as forgetfulness. Those who might benefit from a photo with John Lewis, who might enjoy a statue of Rosa Parks on the grounds of the Capitol, but whose political careers might depend on disenfranchising Black voters and pretending not to see the systemic injustices against which Lewis and Parks fought.

In spite of these glaring contradictions, these infuriating hypocrisies, Lewis remained defiant. “I assume that your word is good until you show me otherwise,” he wrote in Walking with the Wind. “I refuse to be suspicious until I have reason to be. Yes, this sets me up to be burned now and then, but the alternative is to be constantly skeptical and distanced. I’d rather be occasionally burned but able to connect than always safe but distant.”

This ability to connect, this refusal to become bitter, this determination to keep his eyes on the prize, fortified him for decades of struggle. And it made him, as Adam Serwer argued in The Atlantic, far more than just an “icon” of civil rights. “This understates who they were,” Serwer wrote of Lewis, C. T. Vivian, and their partners in the movement. “They were the leaders of an incomplete revolution that remade American society.”

While they “would not have seen themselves this way,” Serwer wrote, “in their imagination and compassion, in their sincere belief in the ideals of the [Declaration of Independence], they surpassed their predecessors.”

***

In March 2016, four years after I first came across that insightful YouTube comment about John Lewis, I was working as a speechwriter for Senator Chris Coons of Delaware. Senator Coons and his team had invited Congressman Lewis to spend a day in Wilmington, Del., and knowing that this would be a special day, I’d done everything I could think of to be there for it.

The morning of Lewis’s visit, we gathered with Senator Coons at the Joseph R. Biden Jr. Amtrak station in Wilmington to await the congressman’s arrival. From there, my colleagues and I followed him and Senator Coons as they traveled from event to event, taking pictures, tweeting highlights, trying to observe and absorb it all.

The weather was gray and dreary, but the day itself was joyful because everywhere Lewis went he brought joy. It’s not necessarily that he was constantly radiating happiness himself; he just seemed to transform everyone he encountered. I’ll never forget the smile on the face of the Amtrak conductor who ran over to shake Lewis’s hand before the train continued its journey north. Throughout the day, I saw John Lewis lift the spirits of person after person with the same kindness, the same presence, the same fundamental goodness that I’d been so lucky to experience in our meeting four years earlier.

At one point, I asked Lewis’s chief of staff if this were typical. “It’s like this everywhere we go,” he replied, with a smile that conveyed a profound mix of compassion, respect, and gratitude for his boss.

The final item on the agenda that day was a public town hall meeting that would be aired live on a local radio station. It had already been a long day. I was exhausted, and all I’d had to do was stand around and take photos. When we arrived at the hall where the event would take place, there were a couple hundred people milling about. The room had that distinct aura of small talk mixed with anticipation. As we walked in, Lewis was a few steps ahead of Senator Coons and the rest of the group, and he paused when he entered the room.

The song playing on the loudspeakers at that moment was “Happy,” by Pharrell Williams. That, I knew, was John Lewis’s song. And I knew that “Happy” was his song because I, like so many others, had watched Lewis dance to it in a video his office shared in 2014 to commemorate the International Day of Happiness. It’s a joyful video. It begins with Lewis smiling and dancing. Following some gentle prodding from his staff, he layers some of his own singing on top. “This is my song,” Lewis says, partially to the camera and partially to himself. “Nothing can bring me down!”

Walking into that Delaware ballroom just as “Happy” was playing was one of those moments of pure coincidence that feels impossibly perfect. When I noticed the song, I walked up to Lewis. “Congressman, they’re playing your song!” I exclaimed. He paused and smiled. “They’re playing my song,” he replied quietly, his tone one of simple contentment.

It was a tiny moment. A fleeting and unremarkable moment on the scale of that day, that year, that long and epic journey of John Lewis’s life. But it said so much. Despite everything he had been through, despite the exhaustion he must have been feeling that day, despite the weight of the expectations of people in that room who all came to see and hear from him, despite all the distance he had marched and all the marching he had yet to do — despite it all, John Lewis paused to take in the moment. To be present. To savor the little bit of joy we all feel if our song comes on when we’re not expecting it.

The world can feel hopeless and overwhelming, and its challenges and obstacles can appear insurmountable. But John Lewis seemed to have things figured out. Fight for what you believe in. Show up for other people. Find moments of joy along the way. And always keep the faith, even if you grow tired and weary.

After the event wrapped up, I walked with Senator Coons, Congressman Lewis, and the rest of the group to take a few more pictures before Lewis returned to Washington, DC. Perhaps in a reflection of the digital era in which we live, I had that YouTube comment echoing in my head. Without a doubt, the greatest living American.

I reached over to shake Lewis’s hand and thank him. “Come by the office in DC,” he said earnestly, shaking my hand and smiling.

***

“I am not without passion,” Lewis wrote in Walking with the Wind, describing his determination to attend school as a child. “In fact, I have a very strong sense of passion. But my passion plays itself out in a deep, patient way. When I care about something, when I commit to it, I am prepared to take the long, hard road, knowing it may not happen today or tomorrow, but ultimately, eventually, it will happen. That’s what faith is all about. That’s the definition of commitment — patience and persistence.”

The passage continued with an image Lewis would later share with me in his office. “People who are like fireworks,” he wrote, “popping off right and left with lots of sound and sizzle, can capture a crowd, capture a lot of attention for a time, but I always have to ask, where will they be at the end? Some battles are long and hard, and you have to have staying power. Firecrackers go off in a flash, then leave nothing but ashes. I prefer a pilot light — the flame is nothing flashy, but once it is lit, it doesn’t go out. It burns steadily, and it burns forever.”

John Lewis was America’s pilot light. Not just for civil rights, though that would have been enough. He was our pilot light for justice. For righteousness. For decency. For kindness. For compassion. For grace. For goodness.

Without a doubt, one of the greatest Americans who ever lived.

A note about this essay

When I sent this essay to subscribers of Reframe Your Inbox, I included the following note.

Getting this article to a place where I felt it said what I wanted it to say was far more difficult and far more emotional than I anticipated. At various points in the writing and editing process I was so caught up in some of Lewis’s writings and videos of his speeches that I would be startled to return to the present and be reminded that he had passed away. Such was, and remains, the power of John Lewis’s voice, life, and legacy.

As part of an ongoing experiment, I wrote the first draft of this article by hand. I was curious to see whether writing it this way would impact how I wrote and thought and connected the different ideas and themes in the piece. I’ll be exploring this more in a future newsletter, but it’s safe to say that I haven’t been this immersed in something I’ve written in a long time.

That, however, may have less to do with the technology I was writing with and more to do with the subject I was writing about. As President Obama said in his eulogy for Lewis, “What a gift John Lewis was. We are all so lucky to have had him walk with us for a while, and show us the way.”