‘Changing our minds is one of the most difficult and heroic things we can do.’

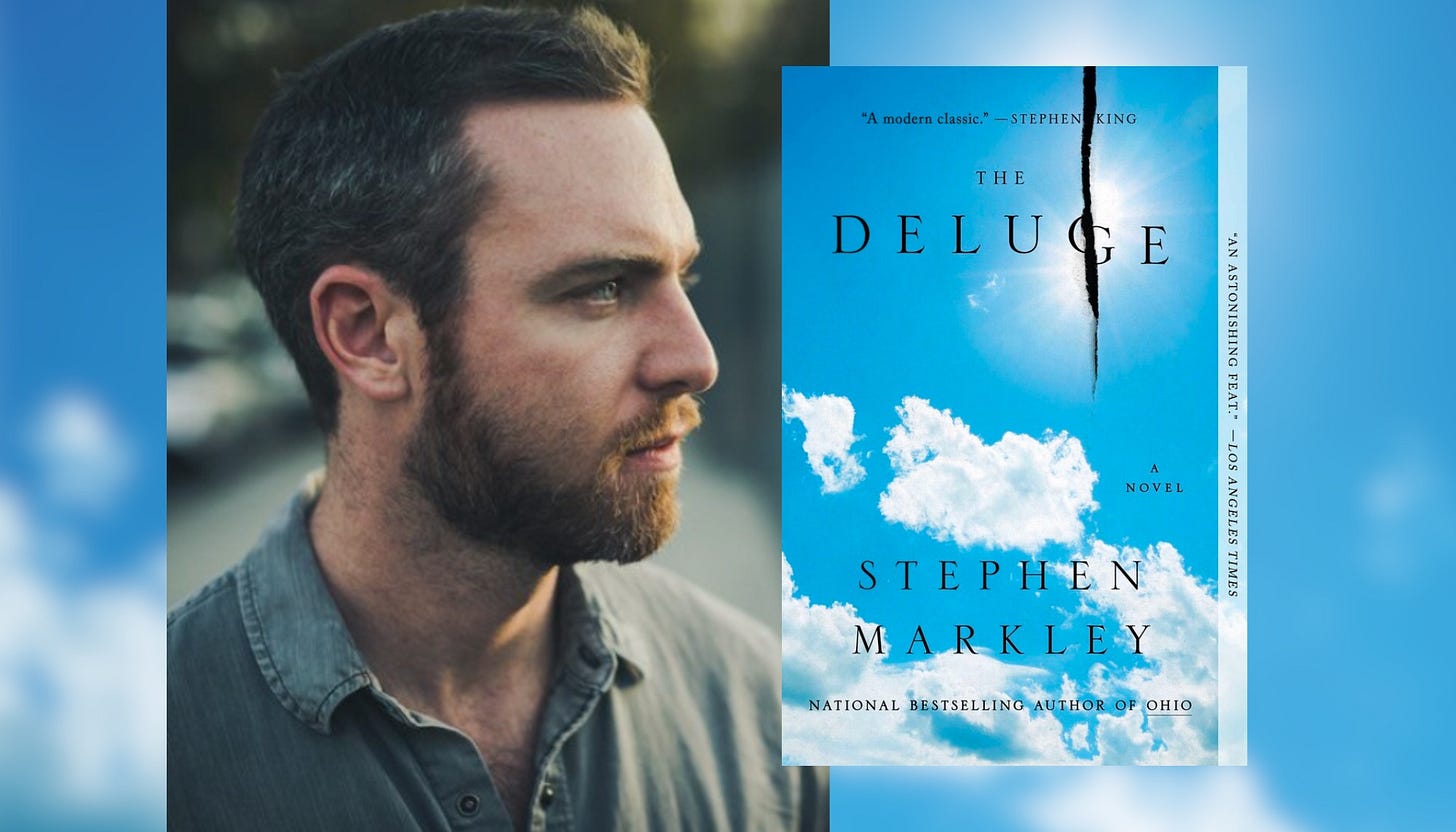

A conversation with Stephen Markley, author of ‘The Deluge: A Novel’

Stephen Markley is the author of The Deluge: A Novel, a 900-page climate fiction epic that imagines, as I described it in July, “an all-too-plausible future of fires, floods, and freak weather events.”

One of the many intersecting storylines in The Deluge is the campaign of the Sustainable Future Coalition (SFC), a fossil fuel industry group, to obstruct climate legislation by portraying its member corporations as the solution to the problem they created. (“We are the Green New Deal,” the SFC’s slogan proclaims.)

When I read The Deluge earlier this year, I happened to be working on a story for The Guardian about the Climate Leadership Council (CLC), a fossil fuel industry-backed nonprofit that is lobbying to replace environmental regulations with a carbon tax. The fictional SFC struck me as not unlike the very real CLC, particularly in how the CLC’s corporate backers appear to see the group: as a rhetorical asset that helps them sell a greener narrative without requiring them to change how they make money.

Markley spent a decade writing The Deluge; he came up with the SFC years before the CLC was born. He told me that the inspiration for the fictional group was the Global Climate Coalition (GCC), the 1990s-era industry body that helped impede global efforts to address the climate crisis. (The GCC was run out of the offices of the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM), a longtime opponent to climate laws and regulations.1 In 2020 NAM’s senior director for energy and resources policy became the head of the CLC.)

Early drafts of my story for The Guardian included commentary from Markley, who is, in addition to a novelist, a climate policy wonk. “I think I’ve been sitting around waiting for somebody to actually ask me about climate policy,” he said at the end of our interview. “Everybody’s like, Where do your ideas come from? And I’m like, I want to talk about carbon prices!”

Space constraints kept his comments out of the final Guardian piece. But in anticipation of the Tuesday, November 7 release of the paperback edition of The Deluge, I’m excited to share our conversation below.2 These excerpts, which are combined from email and phone interviews, have been condensed significantly and edited for clarity.

ADAM: Tell me a bit about the Sustainable Future Coalition in The Deluge.

STEVE: The SFC is the fictional climate advocacy group backed by industry. It essentially exists to delay action on the climate crisis so that its members can continue burning fossil fuels and pursuing carbon-intensive business models. It is a fictional effort to dramatize the very real tactics that industry uses to mold public opinion and policy.

Where did the idea come from?

The SFC has existed in one form or another since scientists and advocates first began speaking publicly about climate, to preempt action. [These groups] almost universally have fun Orwellian names. Other industries have used similar tactics to great effect, and they will continue to do so, I’m sure.

What role did you identify in the U.S. public policy ecosystem that a group like the SFC would represent?

The original model was actually the Global Climate Coalition, a group that existed in the 90s to torpedo things like the Kyoto Protocol.3 They were more of a formal denialist organization, but my take on the matter back in 2013, when I was inventing the SFC, was that industry would have to pivot to a more nuanced approach than outright denial. They essentially have to appear like they’re doing something about the problem in public-facing forums, advertising, and aboveground activity.

A few years back ExxonMobil endorsed a carbon price. And I think everybody is right to sort of roll their eyes at that because it’s so obviously bullshit. This is something I was grappling with in the book: I understood that corporate interests would be evolving in how they are delaying action.

It’s no longer like you can go out in the public square and say the climate climate crisis is not happening. People just aren’t buying that anymore, for the most part. And so to me it was trying to find a way in which they will evolve their tactics.

Do you have any thoughts on the Climate Leadership Council’s policy proposal?

Yeah, I have a lot of thoughts, and you’ll have to suffer through them since you’re the first person to really ask me about deep climate policy. The headline is that the CLC’s proposal is more or less exactly what we should be doing. In fact, it bears a strong resemblance to the “shock collar,” which is the star legislative proposal in the novel.

[The CLC plan] is, and would be, a very effective plan. When I was writing the book, and I was kind of looking for a star piece of legislation—this was around 2011, 2012, after the failing of Waxman-Markey—I was like, Okay, well, I’m going to talk to as many people as I can to design the plan that would work the best and is actually possible.

You’re basically trying to squeeze carbon out of every sector of the economy. And you’re forcing everyone who’s selling goods in the United States of America to also decarbonize as rapidly. A steadily rising price on carbon…would effectively end the viability of fossil fuel extraction as a profitable economic endeavor.

The left essentially gave up on this idea following the failure of cap-and-trade in the Obama era, and fearing the stigma of a tax and the political difficulty of it. [They] shifted to what [clean energy reporter] David Roberts calls “SIJ”—standards, investment, and justice.4 This is essentially what notions like the Green New Deal describe.

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) delivered on the “I” and the “J.” The problem is the “S.” The carrots are politically easy (relatively speaking—the IRA obviously wasn’t an easy lift). But the standards are the hard part. Anything that punishes fossil fuel burning is what the fossil fuel lobby will fight with everything it’s got.

[A carbon tax] is the best policy, by far, and avoids what in my opinion is the biggest pitfall of the IRA: It does virtually nothing to actually punish the business model of extracting and selling fossil fuels. The IRA attempts to create widespread adoption of alternatives, but the carbon lobby will likely spend its efforts on delaying the deployment of renewables, which is why you see them hitting the ground in every state trying to gin up resistance to renewable projects.

However, having said all that, I’m not about to stump for the Climate Leadership Council because I feel like it’s so easy to throw up a website and put up the most obvious thing and say, Yeah, look, we drill for natural gas all over the world, but now we endorse this thing.

My gut tells me that this [the CLC plan] is a plan with no constituency, and that’s by design. Industry and its backers likely need to have a highly reasonable plan to sign on to, so they can pretend they’re trying to do something while filling the campaign coffers of every climate denialist in sight. The Republican Party as it exists right now is a lockstep multi-tool of the carbon lobby, and anyone who dares step outside of that paradigm is going to get primaried out of a job.

If any of these contributing members [corporations that sponsor the CLC] cared about this issue, they could start lobbying the congresspeople they have effectively bought. They could start changing the way they’re donating money and lobbying. I don’t disagree with a lot of what’s on that website. But I question the commitment to it.

My challenge to the CLC would simply be, put a SuperPAC together and start primarying climate-denying Republicans in relatively purple districts. Run a candidate for president in the Republican primary. If you’re sincere about this, if you believe in what you say, start making some fucking noise. We need it.

One of the themes I noticed in The Deluge is the fact many characters are both “good people” and “bad people” at different times and in different contexts. The book seems designed to resist our impulse to immediately categorize people as “good” or “bad,” including the SFC members who very deliberately design a manipulative and deceitful campaign.

My general perception of, like, human reality is that we are all constructing narratives all the time that categorize the world and fit our preconceived notions and biases. When formulating political opinions and tribal allegiances across various issues and political fights, this is totally natural.

As a novelist, though, it’s a trap. One has to think through the eyes of other people, see the world through their lens, and try to make sense of it from scratch. So while I may have pretty rock solid opinions about the people doing the propaganda for the fossil fuel lobby in my day-to-day life, when I sit down to uncover a person as a character in the novel I’m building, I weirdly don’t have the luxury of judging them.

I’m responsible for understanding how they got where they are, how they see the world, and why they think what they’re doing is okay. It reminds me that we all have very little choice in this, that we are a collection of biases and influences and narratives that are more or less handed to us, and that changing our minds, as one character in particular does in the book, is actually one of the most difficult and heroic things one can do.

One of the things that you get into in the book is the classic progressive dilemma of how much compromise is acceptable. [It raises] this [question] of, how much forgetting is going to be necessary and acceptable? How much forgetting is fair? And by “forgetting” I mean what a lot of these oil and gas interests want to do: not talk about how the problem got there but just talk about solutions. Yes, we have to punish oil and gas, at the very least by making fossil fuel extraction nonviable. But at a certain point they have to be involved, somehow, in moving forward. I wonder how you sum up this massive question.

In the opinion of many characters in the book, and in my opinion, what the fossil fuel industry has done is, if not the greatest crime in human history, one of the greatest. It’s close.

The damage they have done already is so incalculable and so difficult to wrap one’s head around, it almost becomes an exercise in futility to even try. The ramifications we’re going to deal with for the rest of our lives, and probably the lives of our children, are so fucking intense. There’s no lawsuit, there’s no jail sentence, that can really undo or make any of this right.

Now, does that mean we don’t try? Of course not. It’s an incredibly difficult sort of ethical and moral dilemma to grapple with. [But] especially after a decade of working on this, my overarching sense is that right now we have to figure out how to stop putting carbon into the atmosphere. And everything else besides that is secondary.

The scale of the crisis and the acute timeline we’re on is so—what’s the word?—it’s so harrowing. And it was done by people who knew what they were doing and did it anyway.

You started working on this [book] a decade ago?

I had the idea in my head for a while, maybe since 2006 or 2007, I want to say. I finally started writing it around 2010. This was basically right after cap and trade failed and Republicans took over the House.

How did you handle the deluge, so to speak, of new policy and political developments over the last ten years, without trying to fit them all into the book?

Basically, that was the hardest part of the book. I call it getting the teeth of the zippers to meet, so the book, when it came out, would feel like it was of our world.

The Inflation Reduction Act passed just as the book was going to press. In the new edition it’s going to have a few sentences here and there about the Inflation Reduction Act passing.

I was basically waiting ‘til the last second to turn the draft in to see if Democrats would get that bill, and then [West Virginia Senator Joe] Manchin was like, No climate bill. And I was like, Okay, that’s terrible, but I’ll turn the book in. And he came back and was like, Oh, sure, let’s do it. So it was really infuriating and made me sweat a lot.

Much like the climate crisis.

Yeah, exactly. I was just trying to keep my eye on the trends I thought were the most likely to develop. And because I was doing my due diligence and my research, basically all the trends that I had envisioned, they came to pass, so that the book was becoming eerily prescient as I was writing, finishing it, and editing it.

Obviously there are small things here and there that I had to tweak and fight and grapple with, but for the most part it’s like the book became exactly what our world is, which is: We’ve made some progress, but not nearly enough. And all the ramifications are growing more terrifying. Our politics are becoming warped. The levels of inequality are creating incredible amounts of agitation and unrest. And on and on and on.

So I think just by keeping my eye on the trends and not trying to predict events, that was how I sort of grappled with it.

https://climateinvestigations.org/trade-association-pr-spending/national-association-of-manufacturers; https://influencemap.org/report/Trade-Groups-and-their-Carbon-Footprints-f48157cf8df3526078541070f067f6e6

https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/The-Deluge/Stephen-Markley/9781982123109

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10584-015-1472-5; https://cssn.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/GCC-Paper.pdf

https://www.vox.com/energy-and-environment/21252892/climate-change-democrats-joe-biden-renewable-energy-unions-environmental-justice