‘We’re made to be outdoors. I want to share that with every single person.’

A conversation with Alison Mariella Désir, author of ‘Running While Black: Finding Freedom in a Sport That Wasn’t Built for Us’

Alison Mariella Désir is the founder of Harlem Run, a New York City-based running movement, and Run 4 All Women.1 She is a co-founder and the former chair of the Running Industry Diversity Coalition. And she is the author of Running While Black: Finding Freedom in a Sport That Wasn’t Built for Us.2

This conversation has been condensed significantly and edited for clarity. To listen to the complete 48-minute conversation, head here, or search for “Reframe Your Inbox” wherever you listen to podcasts.

ADAM: Tell us about Running While Black and why you decided to write it.

ALISON: Running While Black really came out of the murder of Ahmaud Arbery.3

I am a person who, ever since I was, like, four years old, I wanted to write a book. I carried a little notebook around with me and was always scribbling and have lots of really embarrassing manuscripts from the past. So I knew that in my life I would write a book.

I had given birth to my son in July of 2019 and was mostly in the house for ten months because of my own postpartum depression and anxiety and everything that made me fear the outside world. And I finally started feeling like I could leave the house again in February of 2020.

Of course, the pandemic happened right after, and I read about Ahmaud Arbery being chased, hunted down, and murdered in broad daylight. I thought to myself: one, I can’t believe I now have a Black son who this could happen to. And two, There’s no conversation [happening about this in the running world], period—let alone one that contextualizes this.

It started as just an op-ed.4 Then I realized, Nobody’s going to write this book if I don’t write it. It was one of the most difficult things of my life.

You open the book with an excerpt from a piece that Mitchell S. Jackson wrote for Runner’s World about Ahmaud Arbery.5 Because the book is written chronologically, I was thinking about Ahmaud [and] anticipating February 2020 pretty much the whole time. Was that framing intentional?

Absolutely. This excerpt was so poignant to me because it provides this context that I think a lot of the running industry, and people who run, continue to miss: that many people see running as this thing that exists apart from our world, that is a sanctuary, that is a safe space.

For us—for Black people and other marginalized people—we don’t have that privilege to separate our worlds. No matter where we are, no matter what we’re doing, the rules of the world apply.

Bringing in Ahmaud is so central to this book, what happened to him and how he represents what’s happened to so many Black boys and men in history. I wanted the readers to get that glimpse [at the beginning of the book], knowing that we would return to it later.

And it’s also why I opened the book with [a] timeline, because I wanted to offer context—which I guess I spend a lot of my life doing. Things that have been decontextualized or that have been sanitized, I seek to put them in context and tell the true story.

Can you talk about that chronology at the very beginning of the book, where in two parallel tracks you trace the history of running in America alongside the history of white supremacy in America?

That chronology is honestly my favorite part of the book. If you leave [with] anything from the book, you leave with this understanding that there are two different worlds: There’s the white world, and then there’s our existence within it.

The idea for the timeline came from two dates. One was 1896. That, I knew, was the start of the modern Olympics, but I also knew that that was the year of Plessy v. Ferguson. And I knew that the Boston Marathon started around the same time.

I was just trying to make sense of how these things existed in the world at the same time. How is it that the Olympics were happening, which we see as such a progressive thing, as such a unifying thing, at the same time that a law was being codified that allowed for segregation? That really blew my mind. And then with the Boston Marathon, I was like, What? How is this happening?

The other date was 1963, which was the date that Bill Bowerman invited folks to join him at Hayward Field in Eugene, Oregon. Many people cite that as the beginning of what would lead to the running boom.

I looked at imagery from that meetup, and it was all white people, if not mostly white people, from what I could tell from the magazines or the articles. Then I was like, In 1963, we were marching on Washington. We were drinking from “colored only” fountains. We had to sit at the back of the bus.

Again, my brain just couldn’t make sense of it because the way that history is told is really out of context. We talk about this Black history here. Then there’s American history, which is white history. Then we talk about running history. Never really do we see where all of these intersect and understand that all of these things are happening at the same time.

I felt like it would be helpful for the reader to see this juxtaposition, and also have to grapple with [the fact that] at the same time in running history [when] white people were being called outside to do things, to move freely in their bodies, Black people were unable to do that. At every turn, Black people were being restricted, either by legal means or vigilante means.

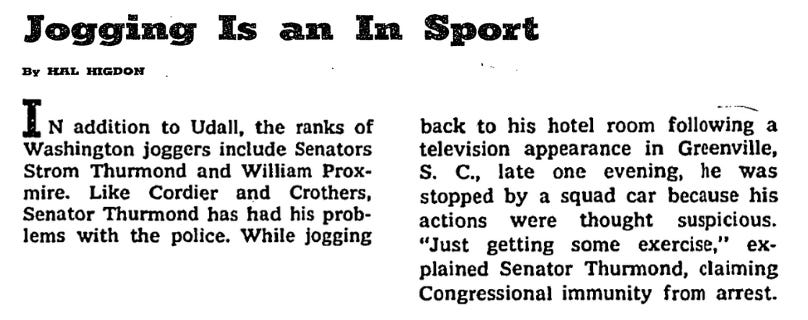

[In the book] you mention a [1968] New York Times Magazine story, which was written by none other than Hal Higdon—the guru of marathon [training] plans, and still a prominent figure in the running industry. In the story about this new jogging “boom,” [Higdon] is talking about politicians who run and cites Strom Thurmond, the South Carolina senator, white supremacist, hardcore segregationist. Then you point out that that story ran ten days after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated.

History is wild. History offers so much information about what we currently struggle with in the present. In this country, there’s an intentional project to erase history and to whitewash it. I think it’s important that as people read the book, they have to grapple with these facts that really seem to make no sense. How could this possibly be? And yet it is the case.

When a white person in particular grapples with that, they can gain some kind of understanding of what it is to be a Black person in this country, where you have to make sense of a world that wasn’t built for you and that is really seeking to at best restrict you, [and] at worst harm [you].

This is a book about running, but it’s also a book about America. [Running] is a lens to see how capitalism works, how white supremacy works, how intersectionality works, how performative anti-racism works. You write, “The sport was not separate from the rest of the nation. Intentionally or not, running was built on the same system and operates within the system.” People who have challenged you have said, Leave politics out of it. Let running be running.

Politics is everywhere. One of the phrases that I live by is that the personal is political. And we know that’s true because every election, what we think of as our freedoms—particularly if you’re a person of color or marginalized—are up for debate.

Like whether women and people with uteruses can have access to abortion. Who can get married, who can live where, what funding is put where. All of those things are personal, but they are political. They’re determined by politics.

When you think about the beginnings of the running boom and the imagery from that time, it’s the imagery that’s recalled by certain brands [today]: this sort of lone wolf, out there, me against the world. This idea of that being the singular narrative.

I have this image of a skinny white guy in really short shorts and a Tracksmith top running somewhere beautiful. That is this romantic vision of what running is for maybe a very small segment of the population, and that segment of the population is so removed from other people’s reality that they don’t understand that they just can’t understand.

My husband recently went for a run, and he was almost run off the road, on purpose, by white kids in a pickup truck. You can at one minute be having this intense emotional moment [while running], getting all of this amazing insight, and then the next minute you’re running for your life because somebody thinks it’s funny to try to run you over.

That is why we can’t, even if we wanted to, keep politics out of running.

You describe the [running] industry at one point in the book as “a big machine that shape[s] the culture of running.” We could look to so many different examples, but I feel like one to start with is the summer of 2020, when, like the corporate world more broadly, the running industry was flooded with anti-racist statements on Instagram. Lots of promises, lots of good intentions. This is an industry that likes to see itself as incredibly progressive. And then came what you describe succinctly in the book as “the regression.”

The industry thinks of itself as being good people who want to get more people in the sport, who want to share what running is about. But when we really think about it, what the industry wants to do is make more money, right? So any concern for more people getting into the sport ultimately has a dollar sign attached to it.

I’m not naive. It’s an industry, so of course there’s money associated with it. [But] you can [still] make money without being ultra-capitalist. It’s not that a sneaker costs $120, and that’s why they sell it for $200. A sneaker costs probably less than $10 to make, but they know that they can increase profit margins. And we know that stakeholders are always interested in making more money until infinity.

That is where there’s this real, for me, crisis of identity in the industry. Couldn’t people still make money without making these huge profits? Couldn’t the industry still make money without knowingly causing harm to people and planet? And, of course, the answer is yes.

But in this country and in many countries, maximizing profits at all costs is a way of life.

As readers of this newsletter might know, I am kind of obsessed with that notion of “good people” and “good intentions.”6 My path to writing about corporate power was through being in a big corporation and seeing everyone who was a “good person.” I think I was a good person. I hope people are good people—I prefer that to malicious people. But it’s not [only] malicious people who have created and perpetuate and benefit from the way things are. It’s the good people with good intentions.

It’s the hardest thing for people to understand. I often do exactly what you do: I talk about how I think I’m a good person. I do my best. I try to make the right decision when I can.

But does that mean that I don’t contribute to, for example, excluding trans folks? I haven’t intentionally set out to exclude trans folks from particular things that I’ve done, but I also haven’t created a space and opportunity.

I’ve been a race director of an event that only had a man and woman category. That was me upholding systems of oppression. I wasn’t a “bad person”—well, whether I was a good or bad person is actually immaterial because the effect is the same.

I actually am talking about this right now in regards to other things within the industry. There’s this big hang up on, Am I a good person? And, Good people can’t uphold systems of oppression. Good people aren’t racist. If that were the case, it’d be so much easier. We would just look out for who’s bad and and wouldn’t hire [those] people and wouldn’t follow those people and wouldn’t allow those people to be leaders.

There are systems that are working. And if we’re not anti-racist, anti-capitalist, then we’re actively participating.

[There’s] something that you wrote toward the end of the book that I’ve been thinking about a lot: “While the work is urgent, it cannot be done urgently.” There’s this comparison you make between endurance sports like running, and the endurance required for a multi-generational fight for justice.

In 2020 and the few years afterwards, it’s like suddenly progressive white people had realized that racism still exists. They’re like, Oh, man, we’ve got to solve this right away. Every Monday we need to have a meeting where we talk about it. We need all the Black and brown people to be sharing their stories. We need to go on this listening tour.

All of a sudden this urgency came for something that, honestly, nobody has ever known any different—anybody who exists in this world. Let me take that back, because this is a construction of whiteness, right? Since 1492, nobody has experienced a world without racism, a world without white supremacy.

So the idea that we’re going to solve this in an 18-month timeframe, which is so corporate, is ludicrous and tires everybody out.

The hopeful part of me is that really no one better than endurance athletes or people who take long expeditions—nobody knows it better than that, right? You have this long-term goal, but there’s all these things that you have to do in the lead up, and you have to actually find enjoyment from those little things that are sometimes very tedious in order to get to that bigger thing.

We as athletes understand what it takes, but can we apply it to bigger issues? I mean, I don’t know. Progressives and Democrats right now have proven that they can’t.

The Boston Marathon features very prominently toward the end of the book. I’d never thought about it the way you describe it, which is [as] a celebration of exclusivity. Can you talk about that?

Oftentimes the most controversial thing [in Running While Black], or the thing that people have most issue with, is my discussion of Boston. And I’m just like, Wow. We are really putting our heads in the sand here.

I think a lot of my issue with the Boston Marathon is the way that the organizers and the race seems to think of itself, and how that leads to the culture that exists within it. It’s this idea that you’re not a real runner or a good runner unless you’ve qualified for Boston. Once you’re a Boston qualifier, then you wear the jacket and you want to let other people know that you’ve qualified for Boston.

It becomes this piece of your identity, of showing that I am this worthier person. And as somebody who went to private school and then went to Columbia University three times, it is the same elitism that you experience in those spaces. You’re part of the Ivy League, and this brand somehow means that you’re more worthy or valuable than other people, and if only those people worked hard, they could do it, too.

All of that is the American dream, the fallacy of meritocracy. All of that manages get baked into this event, and the event continues to get away with it.

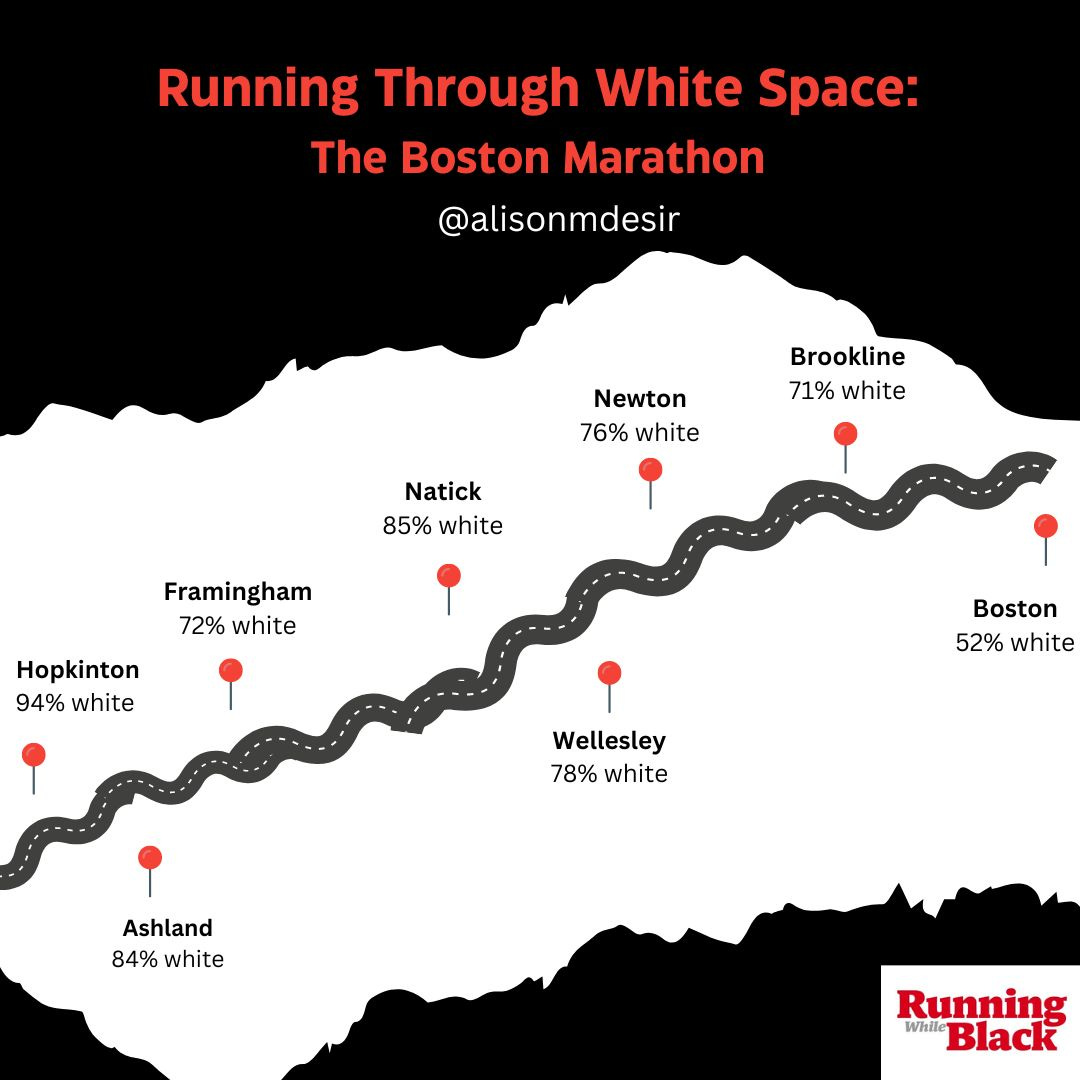

And then there’s all these other pieces that I talk about in this series that I call “Running Through White Space.”7 Boston, to me, is one of the most racist places in the country, despite how much it sees itself as a progressive place. I’m not alone in thinking that.

The Boston Marathon course is built along these small towns that have been highly segregated, that—once the [Fair] Housing Act was passed—then relied on tools like zoning, and continue to. It’s like the Boston Marathon is reinforced by its course and the course reinforces the Boston Marathon.

Can you talk about Running Through White Space and “mile 21” [a cheer zone on the Boston Marathon course]?8 A lot has happened since the book came out.

As I was writing this book, I started thinking about, again, the context of places around the Boston Marathon. I looked at the demographics of the [seven] small towns that Boston goes through. And I ran the Boston Marathon, so I’m familiar with how white the towns are. I made this graphic of the demographics of each of these towns, and all of the towns were [70]-plus percent white.

I started to get curious. How is it that these towns managed to be so white? Because, again, a lot of people think, People just live where they live. The demographics just happen to be what the demographics are. And that’s untrue.

Places remain predominantly white because people in those towns have fought to make it so. Learning about the tools that these towns have used to maintain whiteness, whether it’s zoning, whether it’s language around insiders and outsiders, whether it’s lack of public transportation—all of these ways that they have been able to keep the towns as they are.

Running Through White Space is this lecture that I’ve given that allows people to think about how politics and running intersect.

[In] these towns [on the Boston Marathon course] that you run through that are so white, that have fought so hard to keep them white—what is the impact then when, at mile 21, a group of Black and brown people [are] playing music that is unfamiliar to them? That really is a transgression. It’s like, Who are these people, and what are they doing here?9

And two years in a row: The first year somebody called the police, one of the neighbors. The second year a volunteer on the course called the police, and the entire cheer station was surrounded. The way that the Boston Marathon dealt with it this past year was simply by putting barricades and therefore forcing the people at mile 21 to cheer elsewhere.

But the issue—why is this happening? What is the larger context here? What does this mean?—has not been addressed.

Why are people upset at trap music blasting [at mile 21], but they’re not upset at, like, “Born in the USA” blasting? It’s because of this racial divide, because of the segregation that has existed and the sort of NIMBYism of, We don’t want you here, and your culture is not what is seen as appropriate and certainly not welcomed in our spaces.

I wanted to ask you about something that you wrote about running: “I felt like I had cracked the code to human existence.” I’m wondering if you still feel that way.

I have thankfully had the privilege to experience so many more things. I don’t want to set up this dichotomy: Running was great; now I’ve gone on to these bigger and better things. Running allowed me to find better mental health. It connected me to my body, to my community, and it made me aware of what I could do with my body.

I’ve now moved to the Pacific Northwest. I have this PBS show where I do things in the outdoors.10 And I’ve realized, Man, the world is so much bigger than just running. I really saw running as the end-all, be-all. Now I realize there are, for me, so many other ways to move my body.

I guess I would reframe or rephrase what I said. Moving your body and being outside—that’s the code that I cracked. That is what I work hard to ensure that everybody has access to because there are lots of people who can’t get outside, either because of lack of mobility and lack of accessibility, or because of not having places to be safe, physically [and] psychologically.

That is the thing that I’ve unlocked. We are people who are made to be in the outdoors. We’re made to be moving in whatever way that looks. And I want to share that with every single person.

📚 Alison’s book recommendations:

Just Action: How to Challenge Segregation Enacted Under the Color of Law, by Leah Rothstein and Richard Rothstein11

Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds, by adrienne maree brown12

https://alisonmdesir.com; https://www.instagram.com/alisonmdesir; https://patreon.com/alisondesir

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/675749/running-while-black-by-alison-mariella-desir

https://www.runnersworld.com/runners-stories/a32883923/ahmaud-arbery-death-running-and-racism

https://www.outsideonline.com/health/running/ahmaud-arbery-murder-whiteness-running-community

https://www.runnersworld.com/news/a38334348/ahmaud-arbery-trial-ref

https://adaml.substack.com/p/most-individuals-are-good-people-with-good-intentions-is-that-good-enough

https://alisonmdesir.com/media

https://www.runnersworld.com/news/a43647059/black-spectators-say-police-targeted-boston-cheer-zone

https://www.runnersworld.com/runners-stories/a43878096/my-run-club-was-profiled-for-cheering

https://www.pbs.org/show/out-back-alison-mariella-desir

https://www.justactionbook.org

https://adriennemareebrown.net/book/emergent-strategy