‘The people calling the shots are more interested in corporate power than freedom of movement.’

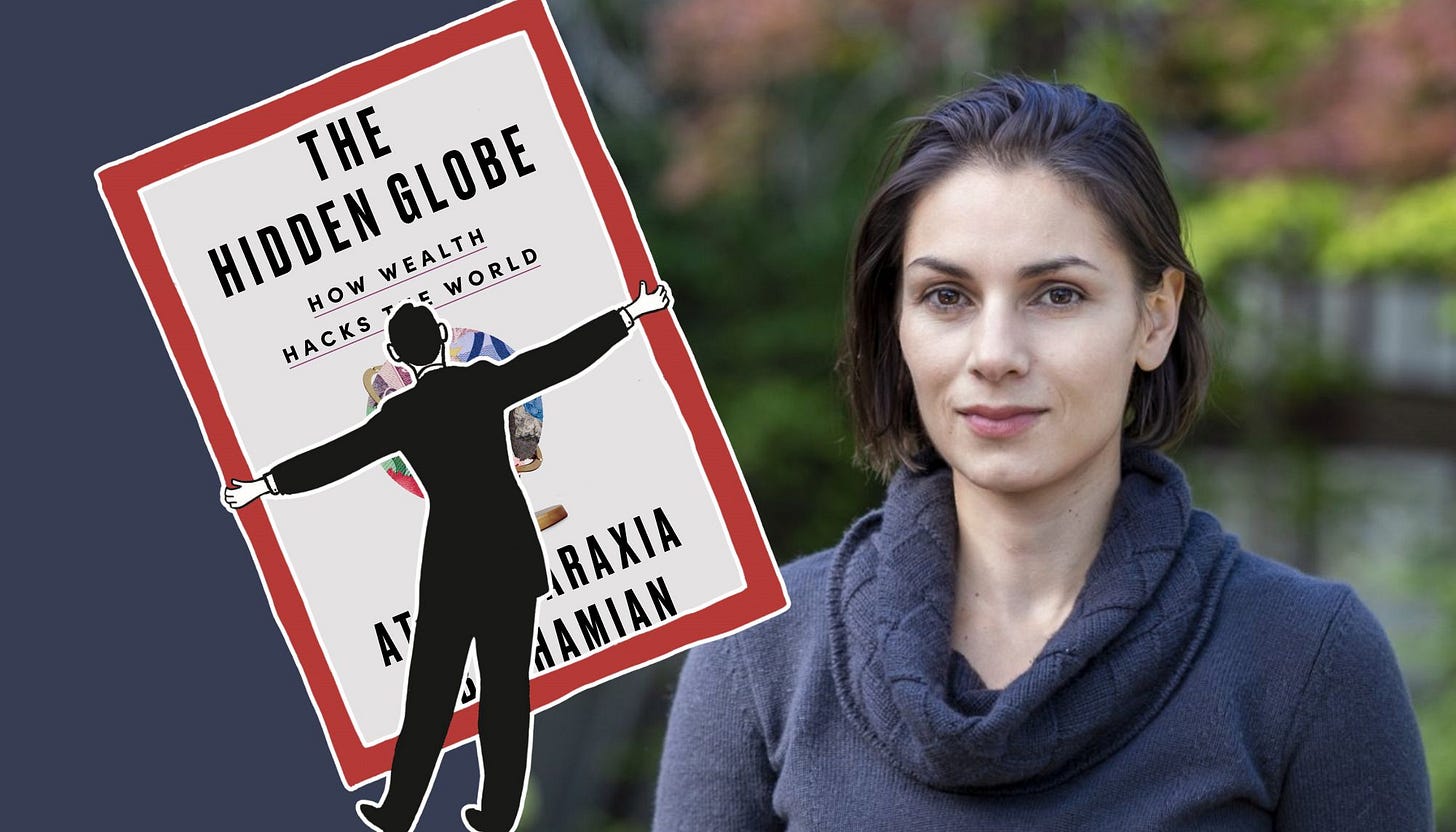

A conversation with Atossa Araxia Abrahamian, author of ‘The Hidden Globe: How Wealth Hacks the World’

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian is an independent journalist who writes about the cracks in the nation-state system.1 A former editor at the Nation and Al Jazeera America, Atossa has written for a range of publications and is the author of the new book The Hidden Globe: How Wealth Hacks the World.2

This conversation has been condensed significantly and edited for clarity and accuracy. To listen to our full forty-nine-minute conversation, head here, or search for “Reframe Your Inbox” wherever you listen to podcasts.

ADAM: [In] the first sentence of the first page you write, “There was something strange about the place where I grew up.” Can you tell us what that is and why it’s so strange?

ATOSSA: I grew up in Geneva, Switzerland. Most people who visit Geneva will say, Oh, it’s very pretty. It’s very clean. What a nice European city. You can see it in a day and then move on.

[But] Geneva contains many worlds within it. It’s the center of international diplomacy: The UN is there, the [World Health Organization] is there, the [International Labour Organization] is there, the [World Trade Organization]. The alphabet soup of agencies.

On the other hand, you have all of the Swiss banks. You have insurance companies. You have shipping companies. Just a huge amount of private-sector wealth.

In terms of the population, something like half of the population was born somewhere else; the other half is Swiss. And on top of that, you have everything that makes a normal city a normal city, right? You have public works. You have city government. You have all these overlapping worlds, and they’re not always talking to each other.

I come from the international community world. My parents worked at the UN. I went to international schools. And for much of my upbringing, I just didn’t have a lot of interaction with the Swiss world or the bank world. It really felt like they were enclaves that people lived in.

This feeling of being in Geneva but not of Geneva—of being somehow apart—stayed with me after I left. I spent a very long time trying to make sense of why my hometown felt so strange to me. It was in writing this book that it all started to come together.

One of the things I liked so much about this book is that you are a character in it. [In] a lot of investigative journalism, the reporter insists on taking themselves out of the story. I love the fact that you didn’t do that, and I’m wondering how that came together.

I felt it would be a bit dishonest to take myself out of the story. You could just go through and edit me out of it—I don’t think that I play such a big role.

But I do think that these topics are quite hard to grasp. They’re slippery. They’re abstract. What is land? What is law? What is territory? What is sovereignty?

My goal with the book, by any means necessary, was to make it readable and human, and part of that involved putting myself into it. You’re not going to read about my innermost feelings, but there is quite a bit of my reflections of navigating this world.

I guess the starting point for the book, beyond Geneva, was that I found myself very drawn to some places that a lot of people don’t enjoy spending time in. I went to Dubai a few years ago. I loved it. I felt very comfortable there.

I had ten very long days in Singapore on a previous reporting trip years ago. At first I couldn’t stand the place. Then I started to understand it and grasp its logic, and it was the same logic as the one where I came from.

The places in this book all share a common logic that I’ve been trying to untangle, and I think that putting myself into it helped untangle that for the reader.

The places in this book together help bring to light what you describe as the “hidden globe.” How would you define the hidden globe?

If you look at the world map that you learn in school, you see almost 200 nation states. They’re all different colors, and there’s very clear borders between them. You can pinpoint where one begins and the other ends. There are boundaries.

What I’m trying to show, in talking about the hidden globe, is that there’s all kinds of territory and space and jurisdiction above, beneath, and between these nations. It can be as small as a diplomatic pouch that a diplomat carries around that is inviolable, that nobody can inspect, [or] something as vast as outer space, which is not even a place—it’s just space.

These places and spaces don’t really figure into our geopolitical imagination. But I think that they should, because when we look at their sheer magnitude and quantity and impact on the world, they actually reveal themselves to be much more significant in a way than nation states.

I’m not trying to say that nation states don’t matter and that they don’t have power, but I think there’s much more to the world than the countries of the world. I think we should be aware of that.

You [write], “The system we all live in is made … to reconcile closed borders with the capitalist maxim of free trade.” Can you talk about how that tension—between closed borders and free trade, [between] the antipathy to immigration and the desire among those with power for capital to flow freely—has driven the emergence of this hidden globe?

The jurisdictions that I talk about in The Hidden Globe, for the most part, are created with the purpose of accommodating capital and capitalists.

Whether it’s a special economic zone that makes setting up a company really easy in Kenya, or an entire new system of law in Dubai that makes it such that foreign businesses can have their day in court, in a court that they are fluent in already, [even though it] is not the local legal tradition, these systems all have the same goal: to make business easier and better and faster and more productive.

A lot of that involves drawing new borders: borders around the zone, borders around this new court, borders around people and property and corporations. Very rarely does the private sector or the UN or any entity in the world endeavor to create new space for people.

That’s because the people who are calling the shots are much more interested in corporate power than they are in freedom of movement for people who maybe don’t have a lot of money or power to begin with.

There is this myth that nationalism and globalism are somehow at odds, but they’re not at all. Globalization depends on borders, whether they’re porous or fixed or malleable. Capital needs them because borders create a vessel for the preservation of wealth. And borders also keep people in their place.

So I don’t think that these two ideas are incompatible at all. They are just the version of capitalist globalization that we live in.

Time and space and what’s real and what’s not start to get kind of murky in these hidden spaces. I want to try to make these somewhat concrete. You note early in the book that “more than half the bags of coffee in the world pass ‘through’ Switzerland.” I’m wondering if you can describe what that means.

Switzerland, and Geneva in particular, is a big hub for commodities trading. If you’re buying futures of coffee, or if you’re buying even physical coffee, chances are, if you’re a trader, you would be doing it from Geneva.

The coffee itself isn’t coming to Geneva. It’s not being sent there. It’s not being processed there. It is merely the specter of the coffee, or the ghost of the coffee, or the financial mirror of the coffee, that is going through Geneva’s desks and traders and institutions and financing mechanisms.

This whole world is rather abstract. You almost have to think of it as: There’s the physical coffee, and then there’s the avatar of the coffee and all of the financial transactions that are associated with it. The avatar is being dealt with by the traders, while the coffee itself might be somewhere else entirely. Things are traded without physically moving. This is the case for probably most commodities.

Can you describe how that process works for a free trade area or a free port? Things are actually “there” physically, but they’re also not [there], for the purposes of law or taxation.

When we talk about free ports or free trade zones, we’re talking about a whole bunch of different types of places. The thing they have in common is that they’re territorial carve outs, where the rules are different.

You might have a manufacturing zone, more commonly known as an export processing zone, where a company would import raw materials, manufacture them into something else, and then ship them off. They would be imported into the country where the manufacturing is happening, they’d be sent to another country, [and then] they would be sent back to where they came from. This is really physical. There are workers, machines, manufacturing, labor.

There [are also] luxury free ports, which are warehouses for very valuable goods owned by people who can afford to have very valuable goods. We’re talking paintings, cars, wine, gold, jewelry—anything that holds value that you can touch, as opposed to a number in a bank account or a futures contract or a bond.

The purpose of the free port in this case is to have a home for these physical objects that have heft and weight and volume, but, at the same time, put them outside the regular legal system of a given country for the purposes of tariffs, taxes, or other regulations that might apply.

These particular rules vary by jurisdiction. A free port in Switzerland will have different rules from a free port in Luxembourg, [which] will have different rules from a free port in Singapore. Each will be more or less permissive [and] appeal to a different clientele or a different wealth base. But the idea is the same: These objects are in a physical space but outside it at the same time.

So many of the things that we take for granted walking around our cities or countries or wherever—things like where we are and what time it is—these aren’t as fixed as we think. These are all political constructs, and they can be changed and manipulated and refashioned.

What we see in these zones is exactly that. The point to remember is that they are being molded or refashioned or reimagined to suit the needs of capitalists.

Accountants and lawyers and management consultants come up throughout the book as key players who help create these zones. Can you talk about the role of these intermediaries in facilitating these spaces and helping propagate them around the world?

We’re all familiar with lobbyists who go to Congress and want to advocate for a certain provision or a certain loophole or tax breaks or business-friendly environmental laws or what have you.

The consultants that I talk about in the book are doing that on the level of territory. They’re going to a government, and they’re helping it carve out pieces of its land to create these industrial zones. Or they’re going to the government and trying to advocate for the country to change its laws in ways that serve industry.

On the one hand, this is very banal, but the particular arenas that the consultants are inhabiting and engaging in are a little bit more exotic than trying to get a pharma company two percent less on their state taxes.

For example, Deloitte was instrumental in getting Luxembourg to pass a “space resources” act, a law recognizing private property in outer space. It’s common knowledge that you can’t get very much done in Luxembourg without a Deloitte or a McKinsey by your side.

These firms are everywhere, and they really play an intermediary role in ostensibly helping the government have better business practices or create opportunities for industry, while also helping industry find a place to settle and put its money and its operations.

One of the aspects of the consulting world that I struggle with is the fact that in so many cases, these privately held companies depend on government contracts and public money and public resources to deliver the profits [and] make the money that they do.

The same is true for a lot of quote-unquote “libertarians” who are interested in these autonomous spaces, free from traditional government control or nation-state sovereignty. The narrative is that they are interested in a world without government, and that “business can do it better.” But their very existence and profits, in a lot of cases, depend on public largesse.

You know how we talked about how the nation state is a container for all kinds of things, including business and wealth? Well, business can do all kinds of stuff. But the one thing that they can’t do yet—on their own, without buy-in from a state—is create the laws that they have to abide by.

Of course, there are always libertarian-style thinkers who want to create their own jurisdictions, whether that’s on a floating platform in the ocean like the “seasteaders,” or in these semi-“charter cities” that are trying to emerge in Honduras.3

What the libertarians haven’t figured out yet is [how] to have quote-unquote “national sovereignty” without nations. So you can go two ways: You can try to start your own. Or, if you can’t beat them, you join them. You co-opt the government’s capacity and make it work for you.

For a long time, Peter Thiel was one of the backers of the seasteading movement, these attempts to create autonomous floating cities in the middle of the ocean.4 I guess at some point he realized that it was probably much more productive and, frankly, cheaper to ingratiate himself to the Trump administration and then, just in case, buy a passport in New Zealand.

That’s the best two-line summary of the libertarian movement over the last couple of decades that I’ve heard.

There are still libertarian thinkers who are having interesting conversations at the level of the thought experiment, and I really appreciate that because it helps us think. But, practically speaking, it’s a tough thing to do.

Whether you’re a libertarian or you’re a communist, it’s really bloody hard to start your own country because the world is not set up to create new countries. It’s set up to keep the ones we have and ultimately to harden their borders. It’s tough. We can rag on the libertarians, but it’s very, very hard to be a morally consistent libertarian.

[From there] it’s easy to go directly into the mindset that I fall into, which is, “Here are these tech players who want to co-opt governments and build these spaces free of democracy.” And [some have] been pretty explicit about that goal.5

But you make a conscious choice [in the book] to be generous toward their worldview in a way that I found refreshing and kind of a counter to my own cynicism.

I think we’re going to start seeing these new forms of government emerge around the world. And I think it’s important to be conscious of what they can and can’t do, and also to not cede them entirely to libertarian corporate interests.

Because at its basis, a decentralized autonomous zone with different rules doesn’t have to be a tax haven, right? It doesn’t have to be a place where labor law is less strict. It doesn’t have to be a race to the bottom. It could just as easily be something else.

To get there, I think we need to be having more conversations about what these places could look like because, I don’t know, man, the nation state is not very inspiring right now!

Of course, these places [other types of government, such as “charter cities”] exist within the confines of the nation state. But if there is some willingness to cede control, maybe there can be something more inspiring than these guys who really like Ayn Rand and want to have fun on the beach.

You write, “To solve global problems in ways that help ordinary people, not just their governments or multinational corporations, we need to be less hidebound to rigid notions of sovereignty, territoriality, and jurisdiction.”

What you were saying about not ceding the concept of charter cities to the most Ayn Rand fringe of the ideological spectrum gets at one of the things I actually found encouraging about the book: Maybe some of these options are the least bad option.

What the least bad option is, is also a function of what the status quo is. And, as the status quo devolves into xenophobia and nationalism and really nasty rhetoric, maybe we ought to give these other forms a closer look and a bit more consideration.

I think we just need to be a bit less precious about what sovereignty is and what sovereignty does.

Reading the book, I hope people will come away from it with an understanding that this idea—that we have one nation with one law and one people and one land—we don’t have that, actually. We have nations with lots of holes inside them and between them. And if you count up all of those holes, or those exceptions, they’re much more numerous and vast and significant than 192 countries.

If we acknowledge that, while also acknowledging that countries are the entities that have the power, maybe we can think of ways to have both at once and negotiate these spaces in a way that is a little bit more progressive.

This is all very abstract, right? Currently, a lot of these free zones, as we’ve discussed, are for the benefit of capital and capitalists. And countries are perfectly happy to cede a piece of territory for that purpose, even though there’s not really a lot of evidence that it works that well and that it brings the country a whole lot in the way of tax revenue or infrastructure.

So that being the case, maybe there’s another pitch to be made: How about building a new city where anyone can show up and live? If you don’t want to have migrants and refugees and asylum seekers and people from “outside” in your country, then why don’t you just carve out some space for them to be not in your country, but also not not in your country?

This isn’t going to solve the bigger problem of nationalism and xenophobia and borders. Full disclosure, I think open borders are the only ethical position. I really believe that.

But given how things are going, maybe the next best thing, or the next least worst thing, is to negotiate some kind of zone for people that, at the very least, helps people be safe and have jobs and earn a living and not put themselves in the amount of danger that they currently do just to cross a border.

You could argue that this is a capitulation to the right and that it is ultimately keeping people out. And that would be true. I’m not going to defend that. But it might help people find a place to go when they can’t live where they came from.

[One] part of Norway called Svalbard is a space for people to go with no [entry] requirements. If they can make it there, then they can go there. Can you describe what Svalbard is and what makes it so unique?

Svalbard is an Arctic archipelago. It’s very cold. It’s very, very remote and close to the North Pole. It’s dark half the year, and it’s light half the year. Not a place that a person would necessarily choose to live. I wouldn’t live there.

But because of a stipulation in the Treaty of Versailles, signed more than 100 years ago, Svalbard is also a place that, while under Norway’s jurisdiction, does not discriminate against outsiders based on their nationality. Which is unheard of.

Most of the time, even in the U.S., we think of everyone being equal. But, actually, the one group of people that everybody can discriminate against systematically are people who are not U.S. citizens.

That’s the case for employment. That’s the case for visas. We don’t talk about it because we don’t think of foreigners as an identity group, I guess. It’s not part of the civil rights movement here to give rights to foreigners. But that’s how it is.

The thing about Svalbard is that it didn’t get that way because of a group of nice internationalists who wanted to create a haven for humanity. It actually happened about 100 years ago when Svalbard was being handed over to Norway, and some coal executives from Michigan who had had business there were lobbying to make sure that their property rights wouldn’t be affected by the handover. Out of this obsession with maintaining their property rights—their coal mines on Svalbard—came this almost miraculous nondiscrimination clause in the treaty, which endures to this day.

I found that sort of encouraging because we have all kinds of nasty coal lobbyists and corporate interests trying to insinuate themselves into lawmaking. And this one time it kind of worked out nicely.

You write, “Svalbard is the only place in the world where anyone, from anywhere, can live: a free zone for people, not just commerce, taxes, or things.” I think [this] surfaces what I found encouraging about the book more broadly.

One of the themes of this book is the idea of rules: how rules are written, who writes them, who follows them, who doesn’t have to follow them. The whole book is a reminder that the way things are is a choice, and we can make different choices. Rules are not fixed. Stories are not fixed. We can tell them differently. We can write different rules.

Svalbard seems to underscore that you can have different ways of organizing people and space that aren’t, by definition, for the benefit of capital—that actually are for the benefit of people. The rules of the world that we live in are changeable.

Yeah. If you accept that it’s all kind of made up, and that we have all these legal fictions that are dictating what we can and can’t do, and also laws that can be changed, why not change?

You know, on the one hand, you can take a nihilistic view where you say, Everything is meaningless and nothing is real. Or you can say, We can create meaning and we can create reality.

📚 Atossa’s book recommendations:

The City & the City, by China Miéville

Legal Fictions, by Lon L. Fuller

Mating, by Norman Rush

Netherland and The Dog, by Joseph O’Neill

https://www.atossaaraxia.com

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/667306/the-hidden-globe-by-atossa-araxia-abrahamian

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/08/28/magazine/prospera-honduras-crypto.html

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/feb/15/why-silicon-valley-billionaires-are-prepping-for-the-apocalypse-in-new-zealand

https://www.theatlantic.com/books/archive/2023/05/crack-up-capitalism-quinn-slobodian-book-review/674064