‘We believe this old story of work. It’s time for a new story.’

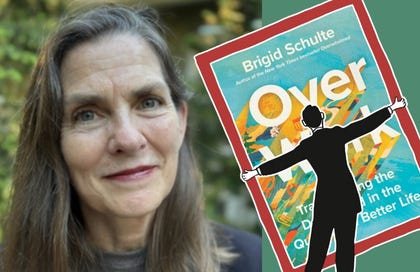

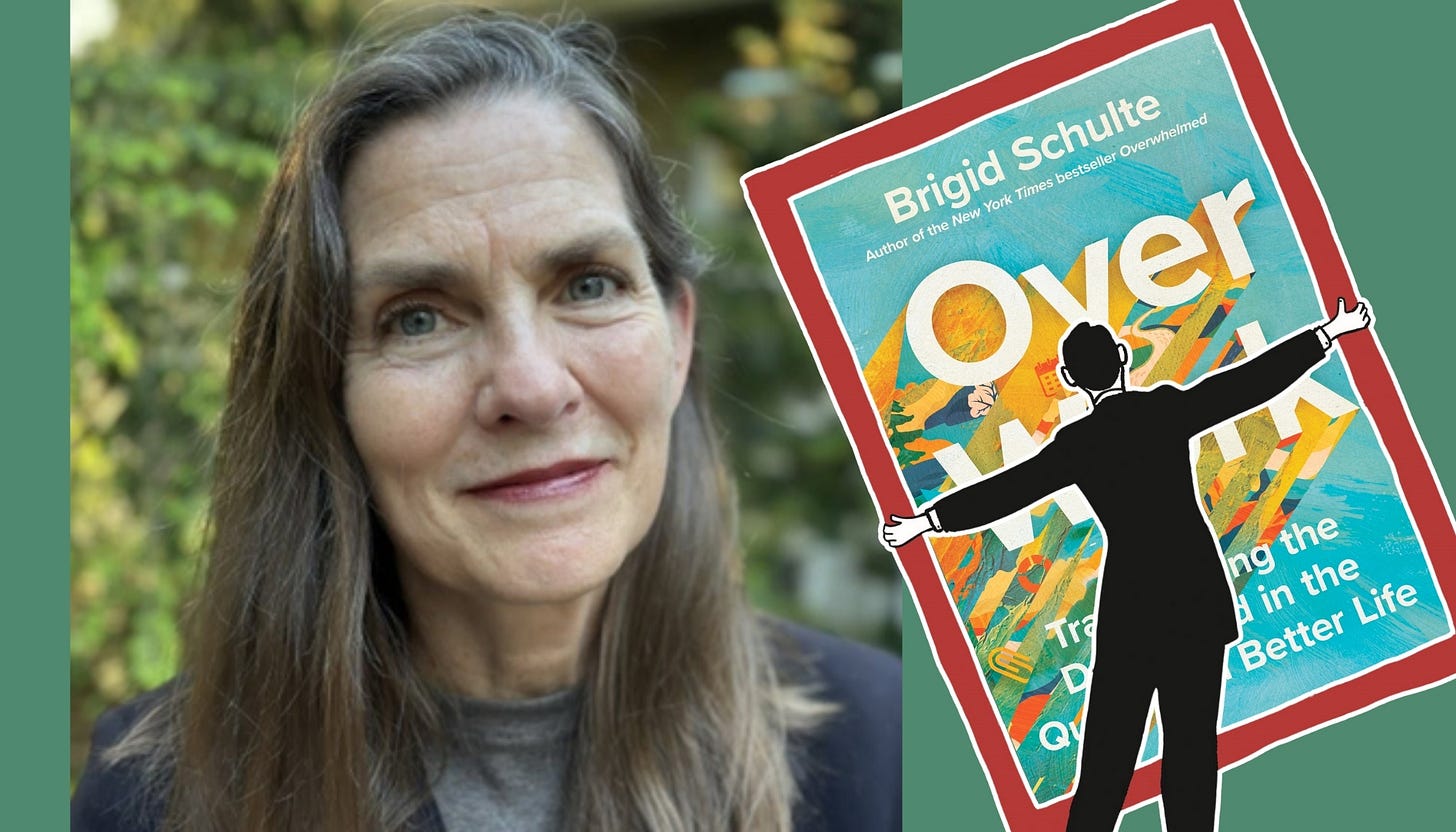

A conversation with Brigid Schulte, author of ‘Over Work: Transforming the Daily Grind in the Quest for a Better Life’

Brigid Schulte is the author of the New York Times bestseller Overwhelmed: Work, Love, and Play When No One Has the Time.1 She is an award-winning journalist formerly for the Washington Post, and the director of the Better Life Lab at New America. Brigid’s new book is Over Work: Transforming the Daily Grind in the Quest for a Better Life, which will be published on Tuesday, September 17.2

This conversation has been condensed significantly and edited for clarity. To listen to our full hour-long conversation, head here, or search for “Reframe Your Inbox” wherever you listen to podcasts.

ADAM: I want to start by asking you about your journey from your first book, Overwhelmed, to this book, Over Work. Can you talk about how the first one led to the second?

BRIGID: Overwhelmed was sort of an accidental book, writing about time pressure and gender and modern life. It was not something that I ever sought out. In fact, at the time, I was working for the Washington Post. I was in daily newspapers. In that culture, you didn’t write about yourself. You didn’t write about if you were struggling as, say, a working mother with kids.

I was really struggling to try to combine work and care and, you know, really feeling inadequate. But you didn’t talk about it. You didn’t even admit it. You had to have this really brave front that you could somehow manage it all.

I didn’t want to use my own story to try to understand why things were the way they were. But I ended up doing it just because it kept coming back. I remember somebody saying to me, I don’t understand why it’s like this, and I don’t have the time or the skills to figure it out, but I will follow you to the ends of the earth if you do that. And so then I thought, Okay, I will take up this challenge.

Why do we make it so difficult for women, for families, for caregivers to be able to combine meaningful work [with] time for care and connection, much less leisure? Why do we so dismiss leisure, particularly in the United States? Why do we think that’s so stupid and a waste of time? That was really the journey of Overwhelmed: trying to understand, through the lens of my own life, why we had come to value busyness as this badge of honor, so that if you felt busy, you felt bad, but you also felt kind of weirdly good, you know?

So then I got to the end of that process. What struck me—it was so clear, by the time I finished Overwhelmed, that so much of the misery and busyness and valuing productivity and all of that, [which] was making people’s lives miserable and difficult, really originated in our work culture. And I also saw that there were such distinct differences depending upon what kind of work you had or where you sat on the socioeconomic scale.

The story that we don’t really talk about in the media or in the business press, that I think is probably more important when you think about the stability of the economy or our democracy or our society—I call it the “crappification” of work. We’ve allowed jobs to become really terrible jobs, even if it’s important work, like care work.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics says that home care workers will be the largest profession in the U.S. economy in the 2030s. It’s such important work. My dad had a stroke and he needed home care workers. That kept him out of a nursing home. It kept him at home. And these workers, they earn maybe 10-12 bucks an hour. Typically, they don’t have any benefits. They’ll have unpredictable schedules.

I found people in those sort of hourly service and care jobs overworking in a very different way [from white-collar “knowledge” workers]. Not [working] in one job like the professional-managerial class, but in a whole host of different jobs, just to survive. And even then survival was difficult: disorganized time, wildly unpredictable schedules—sometimes so unpredictable [that] it’s difficult to find that second job.

You’re asking how I got started on this book. When I started really looking at work, what I saw was not just the cultural factor that I thought I would find—that we find our meaning [and] identity in work, and then we value productivity, so we do more of it. That clearly is part of it. But the more I looked into it, the more I found so many structural and systemic reasons for overwork, just to survive.

We’ve got this really toxic stew of a system that doesn’t work. Basically we’ve got this story that we’re told that we need to work hard in order to not only survive, but thrive. The story just isn’t true anymore. Work isn’t working in that way anymore, and we don’t even realize it. And then we buy this story: Our hard work will save us. It’s really just driving a whole lot of people right into burnout, and it’s not getting you that quality of life that the promise of hard work is supposed to ensure.

I also, in the middle of reporting [this book], got really depressed. I was like, This is terrible. What’s the way out? What could we do?

So many people that I would talk to would just feel like there was nothing they could do, that the change was just too hard, that this is just the way it was, and they were just going to slog through the day and slog through their lives. And I just thought, That can’t be enough. That can’t be the right answer.

And so I began, very deliberately, to search for people who really believed that there could be change—and not just, like, the tips and tricks to manage your day better. Those are important, but that’s not going to solve everything. It might make your own experience a little bit more manageable, but that’s not going to get you a living wage. That’s not going to make sure that you have enough to afford childcare if you need it.

That’s what gave me hope and kept driving me through the reporting process: I want to find more. There’s got to be more people out there. There’s got to be more happening. And I found it.

I talk about being over work. Like, we’re done. We’re done with the way that we’re doing it now. We believe this old story of work. It’s time for a new story.

The subtitle of your book could very well be the subtitle to one of the life-hack, tips-and-tricks [books]. Those are important. I’ve sort of written one of those. I like reading them. But I feel like the people who read those are the people who this book is for.

For people who think that the problem with work is just a white-collar burnout thing, those first couple chapters hit you and say, Yes, that’s bad, and also: Look at everyone else in America who’s trying to make it. That’s such an important reality that you surface. [It’s] really easy for those of us in these more comfortable jobs to miss just how impossible it is to break free.

That became a real driving factor in the way I wanted to present the book. Honestly, it’s been a journey for me as well.

If you read Harvard Business Review or Fast Company or all sorts of business press—and I do, I read them all, lots of great stuff out there—they all tend to be about white-collar professional workers. You would think that we are the only workers that matter. I was so shocked to find a Brookings report—by their estimation, 44 percent of the U.S. workforce is low-wage, earning 10 bucks an hour or less.3 Forty-four percent! That blew my mind.

When you think about the way we report on the economy—GDP, stock market, jobs reports—that’s not where half of America lives. That’s not Main Street. You know what I mean? Half of the people don’t even have a single penny in the stock market. [The] stock market report doesn’t mean anything for them. [Or take] a jobs numbers report. What if the [new] jobs are all at Burger King, or a $12-an-hour childcare position?

We need a much bigger, different conversation about, Why aren’t those good jobs? Why are the CEOs making 400 times [more than] line workers when they used to be making 30 [times more]?4 Why is our tax structure the way that it is, that you can deduct a CEO salary, and stock buybacks are easy to do, rather than investing in your people? Why do we do layoffs? Why do we have this orientation towards shareholders instead of people?

I wanted people to see that we’re all part of the same system, and that white-collar workers need to care just as much about the fate of hourly and service workers. They need to not be invisible to us anymore. If we’re ever going to make change, we all need to be on the same side.

What I sought to do in the book is “galactify” the way we think about work. It’s not just this narrow band of burned out white-collar workers. That’s real. That’s important. That’s the world I know most, obviously.

And yet, that’s one tiny bubble in a much bigger ocean. We need to be looking at the ocean and not just thinking about our own little bubbles.

You mentioned power. That felt like the foundation of this book. Who has power? Who doesn’t have power? Who wants to keep it? Who isn’t allowed to access it? There is a mantra that shows up throughout the book: “policies, legislation, litigation, and regulation.” Those are the mechanisms by which power shifts. Can you talk about that?

Change does come in a lot of different ways. Change is complicated. It can come from worker movements. It can come from consumer movements. It can come from the middle out. It can be a pilot that spreads. I want to acknowledge that change can happen in a lot of surprising ways.

I talked to Jeff Pfeffer, who’s a Stanford business professor. He wrote the book Dying for a Paycheck and was one of the authors of this meta-analysis that was another driver that really pushed me to want to write this book.5

[Pfeffer and co-authors Joel Goh and Stefanos Zenios] looked at 200 work stress and health studies, and they found ten psychosocial stressors. They’re not talking about workplace safety, like falling off of a ladder or tripping over a bucket or falling down a mine shaft. They were looking at everyday things that most workers experience, whether it’s work-family conflict, the fear of unemployment, not having health insurance, if you have a toxic boss or you feel like you’re putting in more effort than you’re getting rewarded for so it feels unfair—this sense of injustice at work. Ten things that I would say most everybody experiences at least some point during their week.

They found that typical, day-in-and-day-out stress was causing both acute and chronic illness to the point where they determined that work itself—simply the way we work—is now the fifth leading cause of death in the United States.

In the short term, it can lead to heart attack and stroke, but more likely what ends up happening is chronic. You work long hours. You get home, you’re exhausted, you don’t feel like going to the gym or for a walk. You don’t really make healthy food. You stop by some cheap fast food place, you collapse in front of the TV, and you do it again the next day. And then over time, that might lead to diabetes or high blood pressure or cardiovascular disease—all sorts of long-term illness that leads to death. And we’re not addressing that at all.

[In the European Union] work stress is illegal. There’s laws and regulations that outlaw the kinds of behaviors that lead to work stress, that makes it either less likely to happen or that it’s going to be addressed, that we don’t have here in the United States.6 Those are really important guardrails.

We are one of the few countries that has no paid maternity leave. That’s outrageous. Germany’s been doing it since the 19th century. We are one of the few that doesn’t have annual paid leave. People call it vacation, and I think that diminishes it. It’s personal time away from work that’s paid. A quarter of U.S. workers don’t have any access to paid vacation time at all. Those tend to be lower-wage workers.

[We] have this policy regime that gives all of the power to corporates and business and says, You can do it out of your own benevolence. If you choose to give your workers health care, if you choose to give them paid vacation days, if you choose to give them paid sick days, you can. It’s up to the employers and their benevolence to offer workers these kinds of—I don’t even want to call them benefits. Other countries, they call them rights. The right to quality of life.

We leave it up to employers, and then many of these same employers create the cultures that prioritize and reward long hours, that reward and prioritize burnout and work-till-you-drop. I mean, over the years working in daily newspapers, the emails that would come from on high: Oh, so and so is amazing. They worked through the weekend. They’ve done it all month long. They’ve worked every single weekend. So and so produced this on vacation. Aren’t they amazing? Then the cultures reward people who don’t use those voluntary policies.

It’s sort of this perfect storm of burnout, where you’ve got low-wage workers who don’t have any opportunity for paid time off to rest and recover and have a life, and then you’ve got the workers who may have access to it through a company policy, but then the company culture prohibits you from actually using it unless you want to put yourself in the spotlight for the next round of layoffs.

[A] story that you talk about in the book that a lot of us, very much including me, have internalized is that these are individual problems that we need to solve on our own. And if we get vacation time or get to go home early or get health care, we should be grateful for it. It felt like one of the goals of this book was to shift the story from, You should be grateful for whatever little tidbits you’re given, to, You deserve this and you should demand this.

Exactly. I was caught up in that as well. I remember after I had my daughter, my second child, I just didn’t see how I could work full time and be the kind of mother I wanted to be. So I negotiated a four-day workweek. I was told, This is going to be the end of your career, if you do this.

And I did—I really “mommy tracked” myself. It was amazing how my reputation shifted once I went to a four-day workweek. I was told, Don’t tell anybody. We don’t want the floodgates to open. It was very clear that I was violating the norms, and that I was no longer seen as a top reporter [who] was going to go places.

I worked really flexibly when it wasn’t okay. There was a time when my son was starting middle school and I didn’t have aftercare for him. I wrote a piece for the Outlook section—which doesn’t exist anymore, sadly—about the secret that nobody ever talks about is that there is no aftercare once you hit middle school, and what do you do with your twelve year old?

I wrote this story, and I got called by the FBI the morning that it came out. This very mean guy said, Congratulations, lady. You’ve just now announced that your son’s going to be home alone at 3:00 every afternoon. So I freaked out and I began working at home more in the afternoons because of that scary FBI guy telling me I was a bad mother.

I was doing that under the radar. I was working flexibly and feeling really guilty about it. But I felt like I owed so much to my employer. There’s actually research—it’s called the “gift [exchange] theory”—that when you feel like these are benefits and that you should be grateful for these tidbits, you end up working more, you give more, because you’re like, Oh, thank God. Please don’t fire me. I’m violating the norms of the ideal worker. Thank you for putting up with me.7 Even though you’re working harder and you might be doing really great work.

I want people to understand that you don’t need to be grateful for these little, teeny, tiny tidbits. We need to feel that we are worthy and that we deserve to have lives as well as good work.

Our public policy is disgraceful. It is designed not to work. Our safety net is designed to make things complicated so that people will be discouraged from applying for benefits because the idea is, You need to work; if you’re not working, somehow you’re laying around in a hammock and you’re lazy.

Let me tell you, one of the eye opening statistics that I came across was a [U.S. Government Accountability Office] report. They found that [of] the people in their study design that were poor enough to qualify for Medicaid and for food and nutrition benefits, 70 percent of them were working full time.8 Seventy percent of the people on U.S. public benefits had such shitty jobs that they qualified for public benefits.

That tells you that workers are not lazy. It tells you that the jobs aren’t big enough to support a human life, and that our public policy doesn’t help them, either. And that made me enraged.

I want people to see the bigger picture, that we’re choosing to make life difficult for people. We’re choosing to keep people trapped in poverty. We’re making those choices based on old stories that we’ve been told that aren’t true.

You point out in the book that this is actually a subsidy that we are providing some of the biggest corporations in the world: being able to pay their employees so little that they require public assistance to be able to survive. That is important and overlooked, particularly by those who make the argument that if you work hard, you can make it, and if you’re not making it, you’re not working hard enough.

It’s really about changing the mindset about who deserves what. Just because you’re CEO, you don’t deserve so much more, such a grotesque share, when you’ve got so many people that are doing the hard work that actually makes your profits.

Toward the end of the book, I became much more interested in learning about the wellbeing economy movement. It’s all sorts of interesting thinkers and economists thinking about, What if we did think about the economy in a different way? What different policy choices would we then make? What different tax policy would we have? What policies, legislation, litigation, regulation would get us to a place where the quality of our lives is really what’s driving our decisions?

If we talk about, Oh, we’re so wealthy, our GDP is this, and the economy grew by X percent, what does that matter if you’ve got half of your workforce barely able to make it? What if you put people’s lives at the center and then really interrogated, What is the policy, what are the decisions that we’re making, that make their lives so difficult?

I think that we all are trapped in this system where we’re so busy and we’re working so hard and we’re looking over our shoulder, running away from the thresher, so to speak, of layoffs, or just running to try to survive. We don’t have time to catch our breath and look around and listen to each other, [to] share our stories and say, You know, things can be different.

So we’ve spent about 45 minutes talking about how this is not an individual problem but a systemic, structural issue, and yet: I wanted to ask you where you’re at on your own overwork journey because your story pops up throughout the book.

I do talk about change on the individual, the organizational, and the policy-political level, because you need all three. And honestly, you have to give people a sense of agency. You can’t just say, It’s all systems and we need to change this. Go vote. That’s too difficult. The horizon is too long. So we do need to think about what we can do right here, right now, in our own lives.

I’m very honest about this in this book, and in the last book as well. It was painful to be that honest, I have to say. But I struggle. I do. I struggle with overwork. I find a lot of meaning and purpose in my work. I’m really curious. There’s more I want to know. I have a hard time putting boundaries and guardrails on it, particularly because I kept working full time while I was writing this book.

I spent a lot of evenings and weekends, particularly when it came to writing. I wrote [in the book] about one beautiful Sunday, writing the workaholics chapter, about [working] too much. My husband came in and said, It’s a beautiful day. Let’s go for a hike. I said, I’ve really got to work. And he turned over his shoulder and looked so disappointed. Well, aren’t you the one that tells people to go play? And I was like, Busted, yeah—but I’m never going to get this book done unless I do this.

I’m here to tell you, I know it’s difficult. And some of it is positive, right? You’re engaged in your work, you find meaning in it, you want to do it. And some of it is negative: There’s too much of it. Maybe I didn’t say no to other stuff. Maybe I should have taken a book leave—well, I didn’t take a book leave because I had two kids in college and tuition is hugely expensive in the United States and I’m super scared about how I would pay my mortgage. There are other factors that drive it.

There are internal drivers, certainly both positive and negative, to overwork and working long hours, and I do have both of those, but it’s exacerbated in our system. Some of that is structural as well. There are a lot of factors that are both individual as well as systemic.

I struggle, but I try. What I continue trying to do is learning to shut things off, making peace with not being done, so to speak. I can use timers, and it’s like, I put in a good day. This is enough.

And I do struggle with that. When am I done? When is it enough?

📚 Brigid’s book recommendations:

The Story of Work: A New History of Humankind, by Jan Lucassen9

Hijacked: How Neoliberalism Turned the Work Ethic against Workers and How Workers Can Take It Back, by Elizabeth Anderson10

https://www.brigidschulte.com

https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781250801722/overwork

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/meet-the-low-wage-workforce

https://www.epi.org/publication/ceo-pay-in-2022

https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/books/dying-paycheck; https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/publications/relationship-between-workplace-stressors-mortality-health-costs-united

https://osha.europa.eu/en/themes/psychosocial-risks-and-mental-health

https://theconversation.com/flexible-working-is-making-us-work-longer-64045

https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-410t

https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300267068/the-story-of-work

https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/hijacked/E7E4A7D850C1E7289BA7AAF910455136