‘White Americans have to recognize how they are complicit in Black Americans not building wealth.’

A conversation with Dorothy A. Brown, author of ‘The Whiteness of Wealth: How the Tax System Impoverishes Black Americans—And How We Can Fix It’

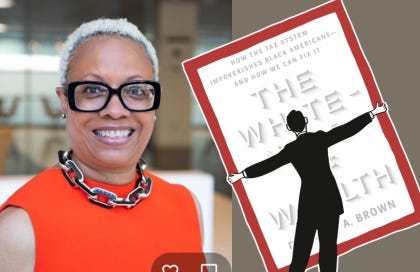

Dorothy A. Brown holds the Martin D. Ginsburg Chair in Taxation at Georgetown University Law Center, where she is a professor of law, and is an inaugural member of the Biden administration’s Treasury Advisory Committee on Racial Equity.1 She is also the author of The Whiteness of Wealth: How the Tax System Impoverishes Black Americans—And How We Can Fix It.2

This conversation has been condensed significantly and edited for clarity. To listen to our full fifty-minute conversation, head here, or search for “Reframe Your Inbox” wherever you listen to podcasts.

ADAM: In the very first sentence of The Whiteness of Wealth, you write, “I became a tax lawyer to get away from race.” Tell us about The Whiteness of Wealth and why you had to write it.

DOROTHY: I actually went into tax law because I assumed it had nothing to do with race. When I ultimately became a law professor for the first time, I actually had the opportunity to read things that I wanted to read, not necessarily things my clients wanted me to read.

I read an article that asked the question, How do you know there isn’t a race and tax problem if you don’t look? I called the author, and I said, I’m going to look. And when I looked, I found that race had a lot to do with taxes, and it completely upended my view of what I thought tax law was about.

I thought tax law—the only color that was relevant was green. And I’ve never been more wrong about anything in my life.

Black Americans began paying income taxes that fund federal benefits long before they were able to receive those same benefits. You quote the journalist L. G. Sherrod, who wrote, “Although we were consigned by law to second-class citizenship, we were still forced to pay first-class taxes.” Take us back to the early part of the twentieth century and some of the key decisions that created the tax code that we still have today.

We start with our modern income tax system that has an origin in 1913. The 16th Amendment was passed, as was our progressive rate structure, which means the higher your income, the higher the tax rate you pay and the higher the tax amount that you pay.

In the very beginning, in the 1920s, the only people who paid taxes were rich, white Americans. Everybody else did not pay taxes. And obviously the people who didn’t like that were rich, white Americans. So as a result, they would litigate.

One issue that they litigated was the tax treatment of investments. And I believe it was in the 1920s that the Supreme Court found that even if you were a casual investor, if you sold bonds or sold stock, you would have income that you’d have to pay tax on. Well, Congress bailed out that rich taxpayer, and [today] we have a preferential rate for capital gains, income from stock.

Of course, that’s a fundamental principle of our tax system today: Income from wages, income from labor, is taxed much higher than income from wealth, income from stock, and that’s due to a rich, white investor getting a tax break through Congress.

One of the consequences of them being so successful lobbying and litigating was that it “made other wealthy Americans aware of the potential to change the laws in their favor.” That precedent feels very relevant today.

Absolutely. Who has the ear of Congress? Who has access to Congress? Who makes campaign contributions?

You tend to see wealthy Americans are more plugged in, have more access, and wind up getting the benefit of more laws than, obviously, lower-income or middle-income Americans, who are barely getting by. Therefore, they don’t have extra money to make campaign contributions, and they’re not always listened to.

You demonstrate, on issue after issue, how our tax code continues to penalize and hold back Black Americans, not through explicit anti-Black discrimination, but rather because the tax code basically just ignores or discounts the Black experience entirely. Meanwhile, as white needs—and particularly wealthy, white needs—evolve, the tax code evolves in response. [This] feels like a particularly insidious form of racism.

It absolutely is, because there’s very little in Internal Revenue Code that mentions race. So when you think about taxes, you don’t think race has anything to do with it. And that’s been the IRS’s story.

When the prior [IRS] commissioner testified in 2020 on Capitol Hill, [Ohio Democratic] Senator [Sherrod] Brown asked whether or not there was any discrimination going on with respect to audits, because there had been some ProPublica research that showed or suggested that there was.3 The then IRS commissioner could say, Oh, no, no, no. We can’t possibly discriminate on the basis of race. We don’t collect the data.

So, when I started researching race and tax, I got a lot of pushback, because people would basically say, What are you talking about? There’s nothing in the code that talks about race. Except, provision after provision—whether I was looking at home ownership, whether I was looking at jobs, whether I was looking at how to build wealth—I saw how the tax law advantaged the way white Americans engaged in the behavior and disadvantaged the way Black Americans engaged in the behavior.

But it really was my book’s publication that brought the idea of race and tax more into the mainstream, so that now you see more people doing research. We had research in January 2023 out of Stanford that actually looked at who was being audited and showed that if you were Black and you filed for the Earned Income Tax Credit, you were three to five times more likely to be audited than if you were not Black.4

Which pushes back on this notion that, There can’t possibly be any discrimination because there’s nothing on my tax return that identifies my race. But even though that’s true, somehow the IRS managed to audit Black taxpayers three to five times more than their non-Black peers.

The fact that the tax code is designed to preserve and grow white wealth undermines one of the common arguments that you hear in these policy discussions, which is that we simply need to make it easier for Black people to buy a home or go to college or invest in the stock market—essentially, get access to the existing system. You write, “Increasing access to a system designed to build white wealth will ultimately not work to build black wealth.” Why do these arguments about access fall short?

Let’s take home ownership, because that’s one of the big ones. Forty-four percent of Black Americans are homeowners, and the argument goes, Well, if more Black Americans owned homes, we’d have a lower racial wealth gap.

The problem is, most Black homeowners do not do homeownership the way most white homeowners do. What do I mean by that? Most white homeowners live in almost all-white neighborhoods. And if you look at market prices that are based on the majority of homeowners, who are white, they want to live in all-white neighborhoods, or almost all-white neighborhoods.

The market reflects those preferences, and those homes are the ones most highly valued. Tax subsidies for homeownership that allow you to sell your home at a tax-free gain if you’re married, and exclude or not pay taxes on $500,000 of income, [are] going to flow to white homeowners. Obviously not all white homeowners, but the homeowners that are most likely to have the greatest appreciation [in home values] are those who live in all-white neighborhoods or almost all-white neighborhoods.

Why do I say that? Because research shows that if your neighborhood has more than ten percent Black homeowners, the value of the home decreases. Why is that? Because that neighborhood is less attractive to the typical white homeowner.

Black Americans, on the other hand, have a choice: Do I live in an all-white neighborhood and be the only Black on the block, or do I live in a racially diverse or all-Black neighborhood? Black homeowners prefer, for the most part, living in racially diverse or all-Black neighborhoods when you ask them [if] they prefer that or all-white neighborhoods, which means Black homeowners live in the neighborhoods that don’t have the maximum homeownership appreciation.

But it gets even worse. Black homeowners are more likely to live in homes or live in neighborhoods where, when they sell their homes, they sell for a loss. And while our tax system advantages gains from the sale of homes, our tax system disadvantages losses from the sale of homes.

White Americans win when they buy homes, not just in the mortgage interest deduction, but when they sell it, they can get a tax-free gain. Black Americans can get a tax-free gain, but they’re more likely to get a significantly lower amount of tax-free gain. And then if they sell at a loss, it’s non-deductible [from their taxes].

Homeownership does not work the same way for Black Americans that it works for white Americans. And most people who think the solution is just increased homeownership don’t understand racism in the homeownership market.

You write in the chapter on housing that “tax policies reward most white taxpayers’ personal choices and punish those made by black ones,” which I feel like could apply to so many of the different issues that you talk about in the book.

Absolutely. I teach federal income tax, and one of the things I teach is, we don’t allow rent as a deduction because you’ve made a choice to rent. We don’t allow commuting expenses as a deduction because you’ve made a choice to not live across the street from work.

We don’t allow rent because we call it a personal family living expense, but we do allow a mortgage interest deduction, [even though you] made a personal choice to buy a home. So the tax law advantages all kinds of personal choices. You make a personal choice to get married. Why should your tax bill change because you get married?

Another one of the persistent and very soothing myths that you dismantle in this book is that a college degree is basically a one-way ticket to wealth and stability and the American dream. There are lots of reasons why this is not accurate for many Black Americans, but I wanted to ask you about one reason in particular, which is resources. You write that “the missing link” in explaining racially disparate college outcomes “is college endowments—and, of course, the tax policies surrounding them that keep selective, predominately white institutions wealthy.” How does that work?

Sixty percent of Black college students who start college do not graduate, but they leave with debt. And the key to college working is, you graduate, you get a degree, and you get a job that enables you to pay off the debt. So if you don’t graduate, you’re already behind the eight ball.

But let’s fast forward to the Black Americans who do graduate college. If you graduate college, Black Americans are more likely to have student debt than white Americans, and they’re more likely to have more student debt than white Americans. That’s a function of parental wealth. It’s a function of intergenerational wealth, or lack thereof.

So a Black person graduates. It’s a college degree, maybe the first college graduate in their family. [They] get a good paying job, but they’re in a family system where their parents were victims of Jim Crow, perhaps their grandparents as well. And they may have siblings that aren’t as fortunate as them.

Research shows that white college graduates are more likely to get money from their parents and grandparents for things like paying [for] college, for example, or putting their children through private school. Black college graduates, on the other hand, are more likely to send money up—send it to their parents, send it to their grandparents, or send it to siblings.

Even if a Black American succeeds—graduates college, has a good paying job—they have more economic resources that they have to use for their family members because of governmental discrimination in the family members’ past.

Selective universities are the ones with the largest endowments. And what most of these selective universities don’t do is make sure that students who go there from low-income families leave with no debt. They could do that. They have enough endowment to do that. But they don’t.

You mentioned the fact that the IRS doesn’t collect or publish tax statistics by race. That was one of the reforms that you proposed in the book, as well as one of the reforms that the Treasury department has started to undertake through the Biden administration’s Treasury Advisory Committee on Racial Equity, of which you are a member.5 I wonder what you can tell us about this committee and what its work and analyses are revealing so far.

One of the things that has surprised me is how recalcitrant Treasury has been to deal with racial equity.

The Treasury Advisory Committee for Racial Equity was appointed, and I naively thought that meant there was institutional commitment to take this full speed ahead, in light of President Biden’s racial equity executive order.6 And I have not found that to be the case.

The Treasury Advisory Committee has, I think, done a really good job of making recommendations to move the ball forward. But we’ve faced a lot of resistance at Treasury. Part of it has absolutely nothing to do with race. Part of it is, Treasury is used to doing what Treasury does, and they’re not used to doing anything Treasury doesn’t want to do.

But the other part of it is, the people who work at Treasury, the day-to-day employees, have no facility with race. When I think about Treasury employees, they’re by and large a lot of economists. And it’s not a well-kept secret that economists do not do a good job with racial equity, unless we’re talking about stratification economists like [Henry Cohen Professor of Economics and Urban Policy at The New School] Darrick Hamilton and [Samuel DuBois Cook Distinguished Professor of Public Policy at Duke University William A.] Sandy Darity.7

Economists don’t get race. They are running Treasury, and along comes this Treasury Advisory Committee on Racial Equity saying, Look, we’ve got to look at this information. We have to do this. We have to do that. And you get blank looks, you get stonewalling, you get bureaucratic delays. You get all kinds of responses. But what you rarely, if ever, get is, Let me roll up my sleeves, and let’s see how we can partner to get this done.

It’s been a disappointment—and this is my view only; I speak for no other member of the committee—that I certainly have had to fight as hard as I’ve had to fight to get any progress whatsoever. It’s been a disappointment. But we’ve had some successes. That’s what I tell myself.

Many parts of The Whiteness of Wealth challenge people like me, which is to say, generally well-off white people who are politically liberal and like to think of ourselves as being allies in the fight for racial justice. A lot of people on the left are determined to surface and understand America’s racist history. I think that’s genuine and that’s good, and I hope we keep doing that.

But you point out throughout this book that this focus on racial discrimination in the past often comes at the expense of seeing—or being willing to see—policies that create and perpetuate racist outcomes in the present. What will it take to widen our focus from history to one that also includes the present? And what does it mean to do that in practice?

One example that I think of is from Richard Rothstein’s book, The Color of Law.8 He said, if it were legal what you’d want to do is give Black people homes in a racially segregated, all-white neighborhood. And if you give the next 10 percent, next 15 [percent of] open homes to Black people, that could be a start—if it were legal.

And my response is, No, no, no. The minute you gave two houses to Black people, the white Americans in that neighborhood would leave. Now, would they leave because they were racist, or would they leave because they were afraid of their property values? My response is, I don’t care whether it’s A or B—they’d leave, which means the property values wouldn’t be as high, and the Black home purchasers who just bought [their homes] would wind up with less equity than they otherwise would.

Part of what white Americans have to do is get real about how they react in a racist system. Do they act like their white peers and benefit at the expense of Black Americans and say, Oh, isn’t that a shame?

You know, I found when I was presenting my research on homeownership to largely white law faculties of homeowners, I got more pushback [on] my homeownership research than, I think, just about anything. It was really hard for them to hear that they were today, in that moment, living in all-white neighborhoods, and that they made a choice to do it. They made a choice to not ask how many Black neighbors they had. They made a choice to send their kids to schools with very few Black students.

Part of what white Americans have to do, if they really want to be an ally, is recognize the ways that they are complicit in Black Americans not building wealth.

The other thing I think white Americans need to do, and I talk about this in the book, is to talk about how whiteness has benefited them. To talk about the down payment they got from a relative. To talk about how their parents pay for their child’s private education. To talk about how they got an interview because somebody made a call. To talk about the ways that whiteness benefits them.

Because most white Americans don’t want to have that conversation, or don’t even think about it, because they’d rather think that it was all merit. They earned it all. They worked hard. And isn’t it a shame that Black people can’t just pull themselves up by their bootstraps the way they did.

But what you find when you pull the thread just a little is that there was a certain level of luck associated with whiteness that was involved in how most white Americans have the economic assets that they have.

You mention [luck] sometimes explicitly in the book, but it definitely runs throughout every piece of the book. You write, “The reality of how ordinary white Americans build wealth…is hidden. … The result is an invisible safety net for white Americans, and yet another generation of black Americans wondering why they can’t get ahead.”

Luck and fortune have played a huge role throughout my life. It’s how I can live in Washington, DC as a freelance journalist. I left college with no debt. I’ve been able to turn to my family and my partner’s family for help when I need it. My partner and I own our house. I’m on her health insurance. The list goes on. I work hard, but the fact that I have these benefits has nothing to do with hard work. It is pure luck.

It’s been a few years since you wrote the book. I wonder how you’re thinking about luck in your work and how it manifests in these topics today.

I think I see it more now than I did then, even. And I see that you just pull the thread a little, ask a couple of questions, and you don’t get too far into a conversation—if you’re taking it seriously—before you find out the role that whiteness played in how someone got to that position or how someone got that benefit. And it’s an uncomfortable conversation, but it’s one that is necessary.

The book that I’m finishing up now is a book on reparations. When I got to the end of The Whiteness of Wealth, I realized we weren’t going to fix this without reparations and without having a reckoning of how we got to where we are. And that’s all I can say about the reparations book, or my publisher will kill me.

[Let’s] look ahead to the next nineteen or so months of federal tax policy. Many pieces of the 2017 Trump tax cuts are set to expire [at the end of 2025]. What is at stake in this fight?

What’s at stake are the continuation of business deductions. What’s at stake is the continuation of a maximum [tax] rate of 37 percent, as opposed to 39.6 percent, on wages. What’s at stake are higher-income Americans paying higher taxes. What’s at stake are deductions for higher-income Americans that the Trump tax cuts were designed to facilitate.

Of course, it’s going to matter who has the White House, who has Senate, who has the House after the November election. But if nothing is done, then we go back to the way it was [before the Trump tax cuts], with one exception: The [lower] corporate tax rates are permanent.9

But, honestly, the corporate tax rate is 21 percent. My response is, Well, let’s start auditing corporations to make sure they actually pay the 21 percent. There have been any number of studies that show the high percentage of large corporations that pay no taxes because of loopholes, or perhaps because of deductions [they claimed that] they may not be eligible for but nobody was able to check because the IRS was underfunded.10

Well, the IRS has gotten some funds lately, and they’re going to be—if they’re not already—in a position to audit corporations to make sure that they’re actually paying their correct tax rate. So there’s a lot at stake. There’s a lot dealing with racial equity that is at stake.

If we just let the Trump tax cuts expire, I think President Biden gets a lot of what he wants. So maybe the answer is a really hard line. What I think the Dems should want is an expanded, fully refundable child tax credit. And if you have to say, We’re prepared to let all of those tax cuts for the wealthy expire if you don’t give us what we want, then maybe that’s what happens until the Dems wind up with three branches of government.

I hope I see the Democrats with a stiff spine when it comes time to negotiate with the Republicans over the Trump tax cuts. I’m cautiously optimistic that we might see the Democrats taking a hard line.

I’m wondering if there is a book that you would recommend.

The book I would recommend is a relatively new book, The White Bonus, by Tracie McMillan. She chronicles her family, as well as other families, and how whiteness has provided monetary value. It’s really a good read.11

https://dorothyabrown.com

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/591671/the-whiteness-of-wealth-by-dorothy-a-brown

https://www.propublica.org/article/irs-now-audits-poor-americans-at-about-the-same-rate-as-the-top-1-percent; https://projects.propublica.org/graphics/eitc-audit

https://hai.stanford.edu/news/irs-disproportionately-audits-black-taxpayers

https://home.treasury.gov/about/offices/equity-hub/TACRE

https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/01/20/executive-order-advancing-racial-equity-and-support-for-underserved-communities-through-the-federal-government

https://www.newschool.edu/milano/faculty/darrick-hamilton; https://sanford.duke.edu/profile/william-darity

https://wwnorton.com/books/the-color-of-law

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/jan/12/corporation-tax-break-lobby

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2024/feb/29/trump-tax-cuts-us-companies

https://traciemcmillan.com/white-bonus