‘Not every positive human behavior is going to make money for someone.’

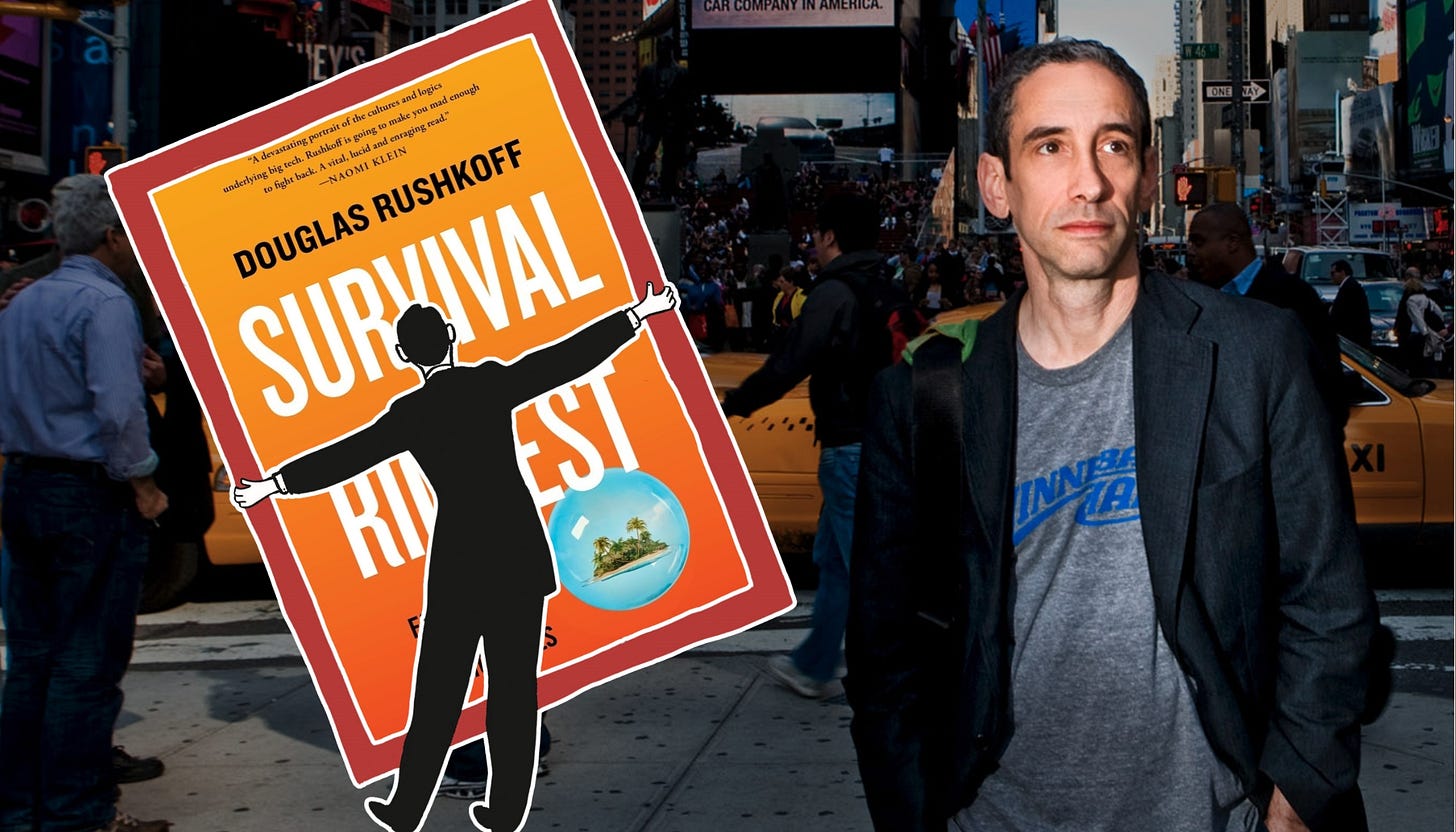

A conversation with Douglas Rushkoff, author of ‘Survival of the Richest: Escape Fantasies of the Tech Billionaires’

Douglas Rushkoff is an author and documentarian who studies human autonomy in a digital age.1 He is the host of the Team Human podcast and the author of twenty books, including Survival of the Richest: Escape Fantasies of the Tech Billionaires.2

This conversation has been condensed significantly and edited for clarity. To listen to our full hour-long conversation, head here, or search for “Reframe Your Inbox” wherever you listen to podcasts.

ADAM: We should start with two definitions. The first is “the Mindset.” The second is “the Event.”

DOUGLAS: There’s a lot of ways of looking at it [the Mindset]. It’s what’s now commonly known as the “tech bro” approach to life, which is that you can somehow earn enough money and build enough technology to escape from the negative impact of having earned money in that way, and [of] the externalities of the very technologies that you’ve created. It’s this idea that with a pedal-to-the-metal, accelerationist development cycle, you can outpace the disasters of your own making.

The Event, as at least the dudes that I met use the word, is whatever that big, bad thing is that renders life on earth impossible, whether it’s pandemics or nuclear war or AI or nano-disaster or social unrest or economic crisis or bloody revolution. Whatever it is that they need a “seasteading” community or doomsday bunker or rocketship to Mars or place where they can upload their consciousness—it’s the undefined thing that happens, usually as a result of runaway capitalism, that forces them to push the escape button.3

The event that precipitates this book is a gathering with five billionaires somewhere in an isolated compound in California. Can you tell us that story?

That’s “the event” with a small “e”—except for, ultimately, my speaking career, I guess. Because by relating what happened there, I think I’ve alienated the kinds of tech bros who think this way.

But yeah, I thought I was going to do just one of my typical talks, trying to get some of these [venture capitalists] and tech developers to change their ways and build for sustainability and a workable world.

My more typical thing is to get hired to kind of be an intellectual dominatrix. These guys know what they’re doing is horrible and hire someone like me to come in and in some way verbally abuse them just a little bit. It’s kind of, you know, Thank you, sir. May I please have another, so then they feel like they’ve paid their penance and can move on.

But in this case, instead of bringing me out from the green room to a stage, it turned out to be just five guys who were brought in. And they sat around this little table in my green room and didn’t want me to do a talk at all. [They] were just peppering me with all these questions about the digital future, like where they should place their bets—virtual reality or augmented reality? Bitcoin or ethereum?4

Eventually they got to the question: Alaska or New Zealand? They wanted to know which is a better place to put their bunker in case of an Event, whether it’s climate or disease or water pollution. Where should they situate themselves? And the rest of this hour I had with them was really me almost comically poking holes in their disaster planning.

They hadn’t really thought it out. They were thinking on the level of kids who watch The Walking Dead. A real prepper understands you prep your neighborhood because everyone’s going to be knocking on your bomb shelter. These guys were looking more at defense. They had Navy SEALs pre-hired to fly out when the disaster strikes and serve as their security force to protect them from the likes of us.

And I remember asking them just to tweak them, Well, why do you think your Navy SEALs are going to take care of you after your money is worthless? If the Event comes, your bitcoin and your tokens and your gold—that’s not going to be worth anything.

They went into a minor panic coming up with these really harebrained ideas for implants and shock collars, or that they would be the only one who knows the combination to the safe where the food is kept. And I’m just toying with them at that point, saying, Well, you don’t think that Navy SEALs know how to get information out of somebody in a bunker? You’re going to spend the apocalypse getting waterboarded by your own security staff.

It was kind of a shock to see that the wealthiest, most powerful people I’d ever been in the same room with felt utterly powerless to impact the future. The best they thought they could do is predict the coming crisis and prepare for its inevitability.

There have always been sociopaths, and throughout history sociopathic characteristics have been rewarded and celebrated. But you write that [today], “those sociopathic enough to embrace [new technologies] are rewarded with cash and control over the rest of us. It’s a self-reinforcing feedback loop. This is new.” What makes this new?

Well, the part that’s new is the amount of power they have over reality. Augustus Caesar could control the lives of a lot of people, but he didn’t really have the ability to end the world. You know what I mean? He could kill most of the people in one place or another. [But] the plague had more power over the potential future of humanity than Genghis Khan or Augustus Caesar or Alexander the Great.

Now our reality is much more interconnected and brittle. Our climate, I really do believe, is at a tipping point. I think that the increase in temperature is not coincidental. I think it’s partly a result of human activity on the planet. So it’s kind of a different moment that way.

Plus, the speed and effectiveness through which their technologies can destabilize our psyches. People really do seem to be mentally and psychologically suffering now. Not just young people [on] social media, but this whole disinformation reality tunnel, which is only going to get more difficult with AI.

It’s interesting. They’ve done some experiments: Put a billionaire in an MRI machine and show them a picture of a starving baby, and the part of the brain that would light up for you or me in empathy and anguish and compassion for the starving baby—that doesn’t light up in the billionaire’s brain. It’s like becoming a billionaire ends up rendering you more sociopathic. And that’s strange.

I don’t know that that’s different [today]. I’m sure that any of those guys were equally sociopathic by the time they became Roman dictators. But when you see a guy like Mark Zuckerberg deciding to emulate Augustus Caesar—that’s his big hero.5 That’s why his haircut is like that. This is who he wants to be: a Roman dictator.

I mean, on the one hand, I feel like we should be thankful that he’s not trying to emulate Caligula Caesar. But it’s still a Roman dictator. It’s still that way of understanding the world, this kind of cartoonish thing.

Elon Musk wants to be like Iron Man. It’s a very childlike drive, but in the hands of people who have arguably more power over the way our culture goes [than ever before]. Elon Musk owns Starlink and the rocket ship company and a propaganda company and an AI company and Neuralink.

It’s not like Rupert Murdoch or William Randolph Hearst owned the media, Rockefeller owned the oil, Carnegie owned the steel. Now you’ve got guys that own all of them. And, again, that’s a bit different.

Zuckerberg ended every meeting at Facebook for a while proclaiming “domination,” right?

“Domination!” Yeah. We could try to excuse it. He was in his thirties. He was kind of a child. But [also] a billionaire with one of the world’s most-used communications platforms tilted toward domination.

Eventually that comes back to bite you in the ass. I think that’s why they’ve got all these doomsday fears. That’s why he’s building this giant bunker out in Maui on the beach there. It’s not just a vacation home. It’s preparation for what they know is the comeuppance of engineering reality this way.

Can you tell us about this “dominator mindset”? It’s something that you similarly explain as both historical and new.

It all goes back to seeing everyone and everything else as a resource, as a commodity—not as a living thing, not as part of oneself, but as there for the taking.

When the colonialists were expanding into the “new world,” they had [Thomas] Hobbes telling them, You don’t have to see the natives in the new world as human beings. They’re not Christian. They’re not fully conscious. They have kind of human-looking bodies, but they’re like animals, like shrubs, like trees, and you can just wipe them away the same way that you’d wipe away trees or a forest or a jungle.

And the irony there is that, one, of course they’re human beings—they’re in many ways more developed than the Europeans who went there—but [also] that you would say, You can just wipe them away the same way that you’d wipe away a forest. Well, you shouldn’t wipe away a forest either, right? A forest is a living thing with a function. The deforestation of the planet is part of why we’re in the big mess that we’re in.

They believed they had moral high ground to dominate, ostensibly because they were Christian or because they were white or because they were European, and everything else is just kind of the wild of nature. That’s the dominator mindset.

[Sociologist and historian] Riane Eisler traces it back to the invention of metallurgy. Before metallurgy, she says, women had much more of a role in society, in leadership, but after metal we made swords and chains. And that’s what led to the male-dominator society. The chains let us enslave people and the swords let us kill people and attack other villages. That’s when the sort of rampant dominator spreading happened.

What ends up happening is we put in systems that require domination in order to sustain themselves. In the late Middle Ages, we started to see the beginnings of a peer-to-peer society. It was after the Crusades. People had gone to the Moorish territories or nations and seen the bazaar, which was this peer-to-peer marketplace. They brought that back to Europe as the market, and they had market day and people would trade with each other and they developed local currencies. People started to get wealthy because they were trading in a circular economy, rather than delivering everything up to the feudal lord.

But then as the feudal lords and the aristocracy got poor[er], they invented money systems that really stemmed or diminished or repressed this rise of the middle class. And one of [these systems] was as simple as central currency. They made all local monies illegal. You’re not allowed to trade with those little poker chips that you invent in your own town. Now you’ve got to borrow money from the central treasury—at interest.

It was a brilliant idea because now the aristocracy could make money simply by having a monopoly on money. Now they were the bank. But what it built into our society was the need for growth. The only way to pay back more money than you borrowed is for the economy to grow.

To this day, we talk about the health of the economy as GDP. The only reason we need the economy to grow is not that we need more stuff, not that we need more houses and more land to get developed. What we need is to be able to pay back the rate of interest, the rate of growth required by the money system.

We have a whole society growing and dominating in order to serve that bank ledger. It worked really well when we needed to expand, expand, expand. But after World War II, it kind of stopped. All those places pushed back. We started partitioning the colonies. It’s when India happened, when the Middle East happened, when Rhodesia pushed back and became Zimbabwe. We couldn’t take more land.

And that’s when they came up with the idea of, Well, the internet can provide more surface area. It will create new markets for growth.

But the territory of the internet is not really just the servers that are out there. It’s the surface area of human attention and human activity. Without some connection to our time and effort and energy, these systems don’t have any value.

We’ve ended up mining ourselves and our psyche for this. What was land and physical [and] political domination has become mental and attention domination.

As you point out early in the book, a lot of this [way of thinking] is not just the techno-saviors at the top. During Covid, folks with economic privilege had the ability, at least to some extent, to separate ourselves from the rest of the world. You ask in the book, “Was it really Covid, or was the pandemic simply helping to justify a trend that was already well in progress?” I wonder if you arrived at an answer to this question.

This kind of isolationist fantasy—you know, I get it. It’s a 14 year-old-boy’s thing: I just want to lock myself in my room with my video games and some ramen and cheese doodles and not do anything else. Covid kind of became the excuse to surrender to the message, or the offer, that I think technology is trying to give us, that you can just swipe left and right and not deal with the messiness of the real world and community and all that.

But for a lot of us, I think, Covid woke us up to the need for contact, for socializing. You could look at even the rise of Trump as a response to this hyper-individuated, sterile online existence. They want to be in a big stadium with a whole lot of other people cheering. Just to be with other people is such a delight. It’s such a privilege. Many of us would take almost any excuse just to hang out with others at this point.

The problem with hanging out, just hanging out with other people, is it’s hard for companies to monetize, unless you’re going to a Taylor Swift concert. What if you’re just hanging out? What if you’re just cuddling? How do you monetize cuddling? It’s really hard.

I started doing this talk called “Borrow a Drill.” If you need a drill, most people are going to go to a Home Depot and buy a minimum viable product drill and use it once and stick it in the garage. Then it probably will never work again.

You’ve spent so much money, so much environmental toxin and slavery and everything else, to get this one drill, when you could have just walked over to the neighbor’s house and said, Bob, can I borrow your drill?

Our reluctance to do that is the thing we have to fight. And I understand. If you borrow a drill from Bob, then do you owe Bob something after that? What if he asks you for something? What if he wants to come over to your barbecue party? Now you’re going to be friends with Bob, and then what about the other neighbors? Are they going to want to be your friends, too? And that’s messy and strange and not why we moved to the suburbs, [which] is to have shrubs and not know our neighbors.

No, no—if you know your neighbor, life becomes way more fun and interdependent. Then maybe you get one lawn mower for the block instead of everyone having their own lawn mower, and each person uses it a couple of hours a week, and you’ve saved all that money and the environmental stress.

Whenever I do that, someone invariably gets up at the end of the talk and says, Yeah, but what about the drill company? What about the workers at the lawnmower company? If people are buying less lawnmowers, then what happens to those jobs? What happens to those stocks? And that’s the ass-backwardness of the system in which we found ourselves.

It reflects the extent to which this way of thinking is so entrenched that, much like neoliberalism more broadly, we don’t even realize that it is a thing that can be changed. We just assume that that’s the way things are.

Right. You know, when I talk like this, people say, Oh, so now you’re saying we have to do degrowth? And I’m not saying we have to do degrowth, but we have to be able to cope with degrowth. Degrowth is not the goal; degrowth is the result of people buying less shit.

But if you really want to grow, you grow in other ways. You just have to assign value to things that we don’t assign value to. Like every plot of land that was saved, every bit of topsoil that you’ve replenished, every child that you’ve saved from mental illness.

I’m not sure where I thought your book was going to go, but I didn’t necessarily expect to move toward a discussion of degrowth. Can you tell us what degrowth is and how regenerative models fit into where we go from here?

You [can] use the aristocracy and the creation of central currency as the easiest way to understand the growth trap, or the growth mandate. Everyone has to use this kind of currency, and to use this currency, you have to borrow it from the central bank at interest. So in order for me to transact with you, we have to use money that requires growth, that requires more be paid back. That “more” has to come from somewhere.

Where does it come from? Either you go bankrupt, or we find someone else—some new territory, some new place, some new land, some new animals, some new labor, some new something. We got to keep going, going, going. Is there ever such a thing as enough in that world? There’s not. You have to keep going. And that’s just incompatible with a finite planet.

Degrowth, which I don’t see as the goal so much as the result, is the acceptance of the fact that not every positive human behavior necessarily grows the marketplace. Not every good thing is going to make money for someone. I know that’s hard.

You could have a conversation with somebody. If you’re just sitting around having a conversation with somebody on a park bench, that’s a bad thing for the market. You’re not in a cafe. You’re not spending money. You’re not in a movie theater. You’re not driving a car. You’re not using gas.

So as people learn to enjoy experiences that don’t cost anything, they are creating a great and dangerous drag on the market. They are enemies of the market, enemies of the state. Why aren’t you spending money? Why aren’t you producing something? Why aren’t you consuming something?

I believe we need to change that. We need to at least admit the possibility that human beings enjoying each other without paying anybody anything is tolerable, that it should be allowed. It should be even celebrated because it’s unique and it’s wonderful. It actually ends up being less taxing on the environment. You may not have to work as much.

How would we deal with a world in which, let’s say, people started to share their tools with each other? So America bought 20 percent fewer tools every year because we’re using each other’s stuff. How do we cope with that? The only way to cope with that would be to start developing economic models that can tolerate slowing down.

Could we tolerate a four-day workweek? What would that look like? Would we allow it? How do we get our heads around that? And that’s tough. That’s really tough.

But I feel like the only way we’re going to get into a world where we don’t need to totally wreck the environment or destroy the coral reefs or raise the oceans by another five meters is [if] we can develop an economic model that can survive without exponential growth. That’s a really tough argument to make in America today.

It’s definitely tough, but at least from an individual perspective, I found it kind of liberating. I think that’s why I finished the book feeling, if not hopeful, a little less pessimistic. Once you recognize that it is possible to live a fulfilling, healthy life, and to provide enough food and water and economic health and well-being for everyone on the planet with what we already have—I found that liberating to hear.

You write toward the end of the book, “There’s no ‘solution’ to our woes other than maintaining a softer, more open, and more responsible comportment toward one another.” And that when you put it like that, that sounds doable.

It should be doable. You know, it’s funny. Our conversation was quite dire, but the book is actually very funny. The book is meant as kind of a black comedy, almost a nonfiction satire of these dudes so that we can laugh at them and then realize that’s not the way we want to go. They are not the winners. They’re the victims. They’re not happy people. They’ve got so much money, but they can’t stop.

I’ve given talks at business schools, and there’s this one where I start the talk by asking, By a show of hands, would anybody in this room be satisfied making $50 million total? No one will raise their hand.

And then I tell them, Okay, the purpose of this talk for me is to try to convince as many of you as possible to be satisfied with a goal of $50 million. I’m going to explain why your business is going to have [a] greater probability of success, why you’re going to get to be a better CEO, and why you’re going to have a better impact on the world, why you’re going to have a happier life, if you can somehow lower your sights to just $50 million—if you can somehow make yourself okay with that as your endpoint.

I know it sounds funny, because for most of us $50 million really is enough. I mean, most of us could squeak by on that, I think—yet these guys [cannot]. It’s losing to them. That’s losing. They need that amount of excess extraction. How can you spend it? What are you going to do? What do you want, planes? They’re the ones who are trapped.

The other direction might sound way more hippy dippy or new age or something, but rather than figuring out how to build a moat with fire around your vacation home, what if you figure out how to be friends with other people around you in your own neighborhood? What if you don’t have to move? What if you have enough?

How can you create a sense of stability and security by having a network of people you love and trust, rather than somehow having enough investment in the bank—or at least both? One doesn’t have to cost you the other.

I wonder if there’s anything that’s changed in the way you think about this stuff, or in how you see the world, since this book came out.

This is strange to say: I feel like I have more empathy for these guys. I don’t think they’re evil, and I try not to portray them as evil, either. I understand the childlike logic that they’re applying. They’re really, really smart about certain things, but they’re like five year olds on another level.

The social reality that many of us see as obvious is [not] so much a part of what keeps them going and makes them thrive. Where they get their emotional nutrition is not from making eye contact with a person or breathing with them. Compassion is not their thing.

When you understand that, you see that this is their way of trying to help and participate and realize a certain dream. And when you look at it that way, I start to feel like rather than annihilate the Mindset, we have to help them integrate that mindset into the greater mix of humanity.

That dominator urge is part of us. It can’t be allowed to lead.

And to that point, they didn’t create the world in which we conflate wealth and business success with expertise and intellect. They just happen to be very successful in [that] world.

Right. And the people that did create that world, for other reasons—they’ve long since left the building.

It’s odd. We’ve got a bunch of tech billionaires who are willing to disrupt one industry or the other, but they’re not willing to disrupt the operating system on which all these businesses are running. They’re not willing to disrupt extractive, growth-based, exponential corporate capitalism.

And that’s a paucity of imagination. That’s what they have to get their heads around: How much more fun would the AI or nanobots or things they’re making be if they also didn’t have to support a company’s exponential growth, if they didn’t have to keep Nvidia’s stock chart going in a hockey stick upward path? But these are guys that read Ayn Rand in high school and never looked back.

There’s ways, I think, to help them to pull back and see a broader perspective. And the way we do that is not necessarily by teasing them, as I did in this book, although I think we need to be able to laugh at their exploits so that we don’t follow them or support them in this effort. But I think they do need a different kind of help, and maybe I could offer that moving forward.

📚 Douglas’s book recommendations (for the tech bros):

The Torah

Cosmic Trigger: The Final Secret of the Illuminati, by Robert Anton Wilson6

https://rushkoff.com

https://wwnorton.com/books/survival-of-the-richest

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/jun/24/seasteading-a-vanity-project-for-the-rich-or-the-future-of-humanity

https://onezero.medium.com/survival-of-the-richest-9ef6cddd0cc1

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/09/17/can-mark-zuckerberg-fix-facebook-before-it-breaks-democracy

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/13/obituaries/13wilson.html