‘That is what I want for everyone: The ability to spend time with people they love.’

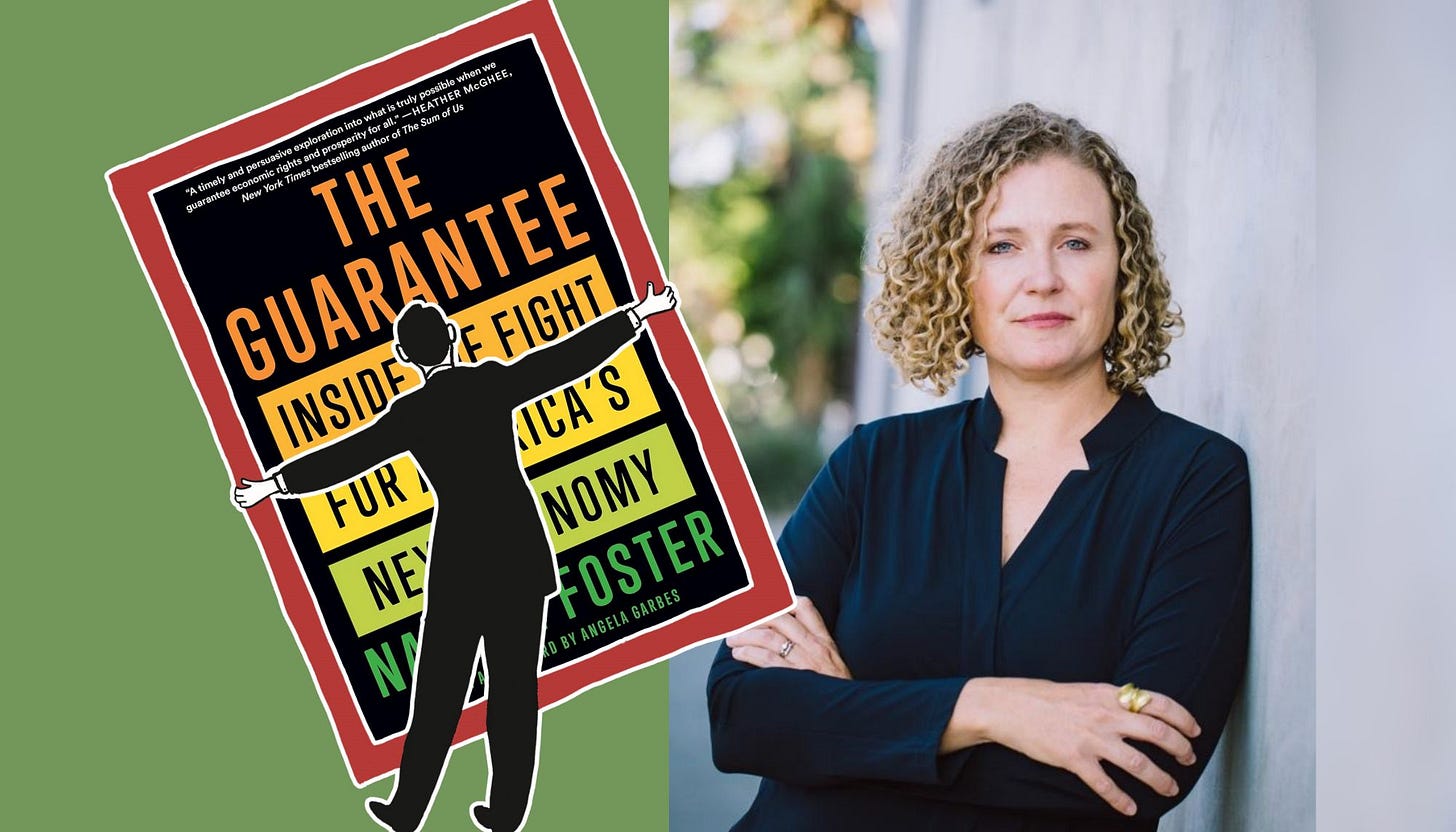

A conversation with Natalie Foster, author of ‘The Guarantee: Inside the Fight for America’s Next Economy’

Natalie Foster is the president and co-founder of the Economic Security Project, a nonprofit network dedicated to advancing a guaranteed income in America and reining in the unprecedented concentration of corporate power.1 She is also the author of The Guarantee: Inside the Fight for America’s Next Economy.2

This conversation has been condensed significantly and edited for clarity. To listen to our full fifty-minute conversation, head here, or search for “Reframe Your Inbox” wherever you listen to podcasts.

ADAM: Tell us about The Guarantee and why you had to write it.

NATALIE: The Guarantee envisions the economy that we deserve in America, where we can have our needs met, regardless of race, religion, or zip code. I call it the “guarantee economy” because unlike the scarcity-obsessed thinking that’s marked the last 40 years, a guarantee economy actually guarantees an economic floor that allows all of us to build our lives of dignity and agency and presence.

I wrote it for a bunch of reasons, one of them being [that] I’ve been heads-down building the guaranteed income alongside [Springboard to Opportunities founding CEO] Dr. Aisha Nyandoro and [former Stockton, California] Mayor Michael Tubbs over the past decade.

As I put my head up and realized just how much progress we’d made on guaranteed income, I realized it wasn’t just income. It was the guarantee of housing and health care and family care and an inheritance—the idea of a “baby bond,” as it’s colloquially called.3 All of those things were moving into the mainstream.

The thing that they all have in common is this idea of guaranteeing an economic floor. I wanted to chronicle the progress we’ve seen in policy, and the heroes, the advocates, the researchers, the writers, the technologists who had moved them forward in ways that were unimaginable prior.

You write early in the book, “The idea of a guarantee itself is not radical. Guarantees are everywhere in America. … They are at the bedrock of our country.” Can you explain what that means?

The idea is that this country was founded on many types of guarantees, some of which we’ve lived up to, some of which we haven’t. But where I find it to be most fascinating is the idea that modern capitalism requires guarantees.

Businesses who function in this economy are given the guarantee of patent rights, of the court system, of our monetary system. Even shareholder liability, the idea that you are not held personally responsible for any misdoings of a corporation—that’s all guaranteed.

Why not extend the concept to everyday Americans, everyday people who make this economy work from the ground up?

You write that “seeing the myths is the essential first step in building something new.” Can you explain what you mean by that?

We have been told a story for a long time about how the economy is like the weather—it is something that just happens to us, that we have no control over. [But] in fact, the economy is like a house that we build every step of the way.

For the last 40 years, we’ve been told a very clear story, that government should get out of the way, the markets will solve our problems, and people should pull themselves up by their bootstraps. If you don’t make it in this economy, it’s your fault. That really was the reigning orthodoxy for decades.

Understanding those myths, I think, is a first step toward a new story that asks what we owe one another as a society and reimagines what freedom, what dignity, what agency can all look like in this next era.

One of the most powerful parts of the book for me was the steady reminder that, yes, [a guaranteed income] is still happening, and, yes, it is delivering results in places like Stockton, California, and Jackson, Mississippi. Tell us about the guaranteed income and what the pilots are showing so far.

What we’ve seen over the past decade with guaranteed income has been really remarkable and is starting to shift one of the myths around who deserves in this country.

About 15 years ago, a student sat in the library at Stanford University reading Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s last book.4 He would make notes in the margins. His name was Michael Tubbs. He would take that dog-eared book of his, Dr. King’s last book, to Stockton, California, where he would become the youngest mayor in American history.

It’s there where I would meet him, and he would pull out that book and say, I want to demonstrate what’s on these pages. Dr. King, at the end of his life, talked about a guaranteed minimum income as one of the ways we could eradicate poverty, and we need to bring that back. And so we would launch a demonstration in Stockton of a guaranteed income.

Around that time, a very important demonstration would launch in Jackson, Mississippi, where Dr. Aisha Nyandoro would spend time with the mothers her nonprofit was working with, Black mothers in Jackson who live in public housing. She would ask them, over and over, What else do you need to make it? And the answer would come back to cash.

She would launch the Magnolia Mothers’ Trust, which would give $1,000 a month to Black mothers who would experience just a bit more room to breathe. In Stockton, Mayor Michael Tubbs would give $500 a month—with no strings attached—to 125 families.

Month after month, those checks would come, and we would find what you would imagine when people feel a baseline of economic security: Their stress levels go down. Their doctor visits actually go up because they’re able to go to the dentist, to the doctor. They find work at double the rate, actually, than the control group—full-time work—because there’s just more space in their life to look for a job. And anxiety levels would go down.

We would open source the playbook. We would invite other nonprofit leaders and mayors in, and it would spread and replicate like wildfire. There would be 20 cities demonstrating a guaranteed income. There would be 40 cities. Sixty cities. It would grow to 150 demonstrations around the country of what a cash floor means in people’s lives, showing what the future of the social contract could be.

Then the pandemic would hit, and lawmakers would look for ideas that were tested and tried and true, and they would reach for an idea that mayors and nonprofit leaders were already doing, which is to give people money in the midst of one of the greatest economic and health crises of our time.

You write, “I found it fascinating how this one idea could potentially speak to and impact so many issues: poverty, racial disparities and economic injustice, climate change, innovation, and of course, jobs and unemployment.” Can you talk about how the guaranteed income touch[es] on many of these challenges?

The thing that’s noteworthy about cash is that it’s fungible, so it means something different to every single person, and how they use it is different every day.

One of the ways that it starts to deal with climate change is that when communities have resources, they’re able to move, they’re able to repair, they’re able to weatherize, they’re made more resilient. We talk a lot about climate resiliency. Economic resiliency is a core part, frankly, of climate resiliency.

[A guaranteed income] is important to employment because when people have a bit more money in their pockets, they’re able to quit a job that doesn’t serve them, that doesn’t pay enough, where the hours don’t work for their lives, where they aren’t respected on the job—and find one where they are.

We saw that in spades in the pandemic. It wasn’t the “Great Resignation,” as it became known by the media. People were quitting, yes, but people were also getting hired. They were finding new jobs in droves at higher rates than they were quitting, leading us to the unemployment numbers we have today, which are some of the lowest on record.

That is power and agency for workers. That comes from having a bit more economic security. Some call a guaranteed income a universal strike fund, or the ability to put more worker power back in workers’ pockets.

Something that you’ve referenced is the power of stories and narratives and perceptions. You describe the old era of neoliberalism or trickle-down economics as “total faith in the market, zero faith in the government, and each of us as individuals left grasping for our bootstraps.”

You write that this narrative “has gaslit us. It tells us that we are to blame. … Yet no bootstraps are strong enough to pull up someone weighed down by decades of a deeply unequal system.” It’s hard to overstate just how deeply this bootstrapping American narrative is entrenched in the way so many of us see the world.

When I bought [my first] house in 2008, I scraped together my savings from [working] as an organizer for the Sierra Club. I would be the first in my family to buy a house. It felt so important for me. The housing crisis, the mortgage crisis, would come shortly thereafter. It would make the house worth [less than] half of its original price. We would be underwater.

I felt so much shame. I just felt dumb. Like, how did I not see this coming? I spent years really feeling like it was my fault when, in fact, the cards had been stacked against me. I had been lied to. Wall Street would construct a house of cards that would fall down on top of me and millions of families like me.

And I was one of the lucky ones. I, ultimately, after a decade, would pull out of that situation. I’d sell the house. I’d be fine. Black and Latino families during that era would lose half of their collective wealth. Ten million homes would be lost during that period. So many of those people felt like it was their fault.

That’s exactly what the story wants us to do. That’s exactly how you can continue an era of trickle-down economics for so long, despite the evidence that it’s not working, that it does not offer widespread prosperity, [that] it does nothing but exacerbate the racial wealth gap—one deeply immoral fact of the modern economy.

One of the things I’ve been reflecting on, and I’ve heard so much from people, is talking about the shame they feel when they don’t make it in this economy that’s, frankly, rigged against us. And that shame has a huge impact on us: how we interact with institutions, how we interact with other people, how we judge other people and what they may or may not be doing with their own income.

Part of what a new story offers us is the opportunity to have stability, have a floor that allows us to live lives of dignity, to provide for our families and our loved ones, the people around us, our community. When we have that, we feel more inspired and can trust and engage with institutions more and engage in the political process and then have more of the economic pie. You can see the upward spiral that’s possible with something like the guarantees.

The [Covid-19] pandemic provides one of the central case studies [of guarantees in action]. And of all the people you could cite, you cite Milton Friedman—the icon of trickle-down, neoliberal thinking—and his notion of ideas “lying around.” Can you tell us what Friedman meant by this?

He has this quote: “Only a crisis—actual or perceived—produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around.” You have to have the ideas, the intellectual underpinning, the power, the advocates, the evidence base around those ideas.

That is what happened in the pandemic. There was an aperture that opened to say, Government has a really important role in ensuring a floor for people in this country, and the markets are not going to solve all our problems. And bootstraps don’t make any sense here. We are all deeply interconnected, and in order for people to be able to build lives of dignity and agency, there’s a baseline that has to be provided. All of that became possible.

[During Covid] we would actually pass the expanded Child Tax Credit, and we would mail every parent in America checks. We would mail rental assistance and mortgage assistance to keep people in their homes. We would pass a national eviction moratorium, which held people safe in their homes during this period of crisis. We would even do things like purchase hotels and move the unhoused in off the streets, giving people a room of their own with a key. That is the type of thinking we had around housing.

With health care, we would do things like mobilize the National Guard to put free vaccines in people’s arms. We would mail tests to every home in America via the postal service—for free. We made Covid care essentially free.

And we would expand health insurance, and it would catch millions of people who would be out of work overnight. In America, [losing your job] once meant you also would lose your health insurance. Now people would roll onto Medicaid, and we would see the lowest number of uninsured Americans in history, getting us closer to what a health care guarantee could look like.

We would have a clearer understanding that care—care for elders, our aging parents, care for our children before they go to school, care for the disabled—all of that care would be the type of work that makes other work possible. We would understand it as infrastructure. We would build policy around it, and many states would take the resources that would come their way and make it a reality.

We would see all those ideas move in to the mainstream and become policy, in many cases. And so, to me it was very important to say, This didn’t just happen. This wasn’t handed down from on high by this administration. No, it was ideas that had been tested and tried and built, that were then moved forward in the pandemic.

One of the things that I kept thinking about while I was reading your book is that some Americans already have guarantees. I have had a guarantee for pretty much all of my life. I have always had a financial backstop and, in turn, the professional and personal stability that follows. What that means is not just financial resources, but I have always known that someone will catch me if I fall.

A lot of people in this world [of policymaking]—politicians, executives, elite decision-makers, and particularly those who are white—are much more likely to have benefited from similar guarantees at some point in their lives. I say all of this to ask how you think about that when it comes to reaching these politicians and executives and elite decision-makers, and communicating with them and getting them to fight to give others what they already have.

What I heard you say is, I’ve been able to take risks and take on lower-paid work that was meaningful to me because I knew that there would be a backstop there. That is exactly what I want for every child in this country. And that’s what this country should want for every child in this country—yes, for moral reasons, and they are wide and they are real, but also for economic reasons.

This country will do better when we’re able to harness the ingenuity and the risk taking and the creativity of the next generation. [Harvard University economics professor] Raj Chetty talks about “lost Einsteins,”5 this idea that there is genius that is evenly distributed amongst the population [but] that is very unevenly harnessed. When you’re working two jobs, three jobs to put food on the table, there’s no exploring your genius. We lose out so much on the brain drain of our own making due to economic precariousness.

I do think venture capitalist Roy Bahat’s framing of [an economic] floor as a “trampoline” is accurate. People have the ability to jump higher when there is a cushion there, when there is economic security. It’s not a net that holds them still. It’s a trampoline that lets people fly.

We saw that during Covid, too. For decades, this country has had a decline in small business creation. As corporate concentration has gotten more serious, it’s become harder and harder to make a mom-and-pop shop pencil out. As people have had to work two jobs to put food on the table, there’s no creating your own business.

During the pandemic, when people had more cash in their pockets, we saw small business creation go up 21 percent in 2021 and 2022. That is the type of dynamism that’s possible when we invest in our communities, in our families, and in individuals. That gets harder the more economically brittle we are as a nation.

You note repeatedly that guaranteed income, among the other guarantees, is not just about wages and benefits, but about predictability and stability and respect and autonomy. How do you think about [the] idea of dignity?

So often we get asked, How do people spend the money? We say, Well, people spend the money exactly how you and I would spend the money. When they get that $500 check, they pay the bills, they buy groceries, they pay the electric bill, they put money toward rent.

The interesting question is what doesn’t show up on the ledger. It’s things like time. The time people can buy with an extra $500 or, in the case of the guarantees, an economic floor, and who they spend it with, and what they do with it.

One story that really stuck with me as a parent was the story of Tomas, who was one of the early recipients [of the guaranteed income] in Stockton, California. The first month the check came in—he had multiple kids, he worked two jobs and then a third job on Saturdays as a mechanic—he just sat on that $500 because he didn’t believe it was possible. It’s too good to be true.

Then the second month, he thought, All right, this is coming. That’s good. So he spent a little bit, but sat on it. The third month, the fourth month, he started to believe that this was possible. He was able to quit his job as a mechanic on Saturdays with that $500 and just spend more time with his family.

One Saturday, he took his kids to the swimming pool, and as he watched them swim, he sat on the side of the pool, and he thought, I didn’t know my kids knew how to swim. [He] had never been able to spend a leisurely Saturday morning with them. Tomas had always been working.

That really struck me as a parent, as somebody who does have those Saturday mornings: That is what I want for everyone. The ability to spend time with people they love, to provide for their family—that is dignity. And dignity comes from stability.

How do you think about the role of fiction in helping people envision new rules and new systems and new stories?

[Author and organizer] adrienne maree brown says, Organizing is speculative fiction. Organizers ask people to imagine a world that does not exist today and to fight for it. And that seems so apt.

I was really honored to have [novelist] Kim Stanley Robinson, one of the great speculative fiction writers of our time, read this book. Here I am—I’m writing about the world that we live in and organizers who are pushing it forward. I’m writing about something that is decidedly not speculative fiction, but of people who are imagining something different.

What’s your take on that?

I’ve written a fair amount about the power of climate fiction and dystopian fiction.6 I’ve seen how that impacts my worldview. [It] certainly can feel very bleak. But it’s also expanded the aperture of what I think fiction can do.

Reading a lot of pandemic novels or climate catastrophe novels, and then moving from there to some of the more hopeful stuff—it underscores a lot of what you’ve talked about, which is the power of story to help us not just build empathy but also see that other realities are possible.

I feel like [Kim Stanley Robinson’s] writing perfectly embodies this. It’s wonky, it’s realistic, it’s gripping—but it’s also hopeful. I won’t say “optimistic,” because it doesn’t say, Things are definitely going to be fine, so don’t worry about it. It says, They could be fine. We can make them fine if we choose to do so.

So much of policy is downstream from culture, and one thing policy wonks get wrong is forgetting that, and how important the cultural stories are. Frankly, it’s one thing that gives me hope because when I look at storylines in so many TV shows today, there is a clear understanding of race, of gender, of what is stacked up against us and how we persevere.

I think of some of the work that [the nonprofit] Caring Across Generations has done. Ai-jen Poo, the legendary leader of Caring Across Generations, [has worked] with Hollywood script writers [to talk] about care storylines.

Even a show like This Is Us, where you have a number of family members and an aging parent, and how care becomes central to that family as they sort out the aging parent and how they’re going to care for her and how they pay for it, how they set it up, how they negotiate it. All of that is a reflection of what so many families across this country are feeling. I think that there [are] a lot of bright spots in culture that show us that this multiracial, democratic experiment that we’re all part of, is possible.

Now, there’s also a lot that flies in the face of that, so I try and remain on the hopeful parts. [Organizer] Mariame Kaba says, Hope is a discipline, and that has always rung in my head as accurate. Some days I wake up and I think, I don’t know. I don’t know. But it’s a discipline to stay hopeful in the face of the significant challenges that we’re facing.

Last question for you is if there’s a book that you would recommend for readers and listeners.

Yes. I’m going to give you two. My book, The Guarantee, shares a book birthday with Joseph Stiglitz’s The Road to Freedom.7 He’s a twice-Nobel Prize-winning economist in his eighties, who is getting to say, I told you so, because he has always challenged trickle-down economics and neoliberalism. His book is a play on The Road to Serfdom, an early neoliberal tome. [Stiglitz] calls it The Road to Freedom, talking about the freedom that’s possible with economic security.

[That book is] paired up with Mia Birdsong’s book, How We Show Up.8 It was published in the pandemic, and has a really important analysis of the freedom we get from community and our interconnectedness with one another. Part of Mia’s project right now at her institution called Next River is reimagining a hundred-year vision of interconnected freedom.

These two books paired are really important for how we reclaim and newly understand the freedom that comes from economic security and the guarantees.

https://economicsecurityproject.org. Many thanks to Lisa R. for introducing me to Natalie.

https://thenewpress.com/books/guarantee

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/23/opinion/ezra-klein-podcast-darrick-hamilton.html

Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? (1967)

https://www.hks.harvard.edu/centers/mrcbg/programs/growthpolicy/lost-einsteins-how-exposure-innovation-influences-who-becomes

https://longnow.org/ideas/memento-mori-books-civilization

https://wwnorton.com/books/9781324074373

https://www.miabirdsong.com/how-we-show-up